—284→ —285→

Universidad de Bielefeld

In the history of scientific research sometimes the aspects of specialization, sometimes the aspects of integration dominate. In the first case development leads to special branches of knowledge with welldefined methodology, however, in general with a small object domain; in the last case interdisciplinary fields of knowledge result which permanently struggle for clearing the questions of their object domains and of an adequate methodology. At present in the history of research into verbal texts the aspects of integration seem to dominate with all advantages and disadvantages. Linguistics, rhetorics, poetics, stylitics, cognitive psychology, ethnomethodology, artificial intelligence research -to mention only the most important ones- in their permanently influencing each other contribute more and more to the establishment of a textological frame-work which serves to investigate the -as they appear, unseparable- aspects of texts.

—286→In our present study we want to discuss some aspects of a central textological topic, namely text constitution (the organization of the verbal material of text).

First we will treat the constitution of signs in general, searching for the most general properties of them which can be extended to any kind of signs of any complexity. We will also analyse the possible objects, types and goals of the interpretation of signs.

Then, on one hand, we will treat those basic notions which, to our mind, are of central importance in the analysis of text construction (the organization of verbal and represented material of text). On the other hand we will treat the question, which representation languages are needed for being able to carry out text interpretation in an intersubjective way and to describe the results of text interpretation explicitly.

After having explicated the basic notions we analyse some aspects of the constitution of a given text, where the analysis will be confined to the levels on which the analysis can be performed without having to apply more complex representation languages.

In the concluding remarks we want to point out some actual questions of the strategy of textological research.

In order that the basic questions of text constitution can be treated adequately, it is first of all necessary to discuss the most important aspects of signification, sign and interpretation.

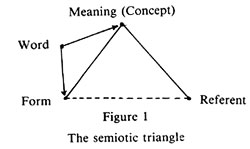

1.1. The relation signification exists in its most general sense between an object declared/accepted as a significans and the object signified/to be signified by this significans. It is usual to demonstrate this relation by means of the so-called semiotic triangle.

1.1.1. The semiotic triangle is represented e.g. by Lyons in the following way (Lyons 1968: 404, here Figure 1).

This representation, with a slight alteration in terminology, mirrors the views of the medieval grammarians which Lyons characterizes as follows:

The terminological alteration involves the more general term referent used by Lyons to replace the original term thing in the semiotic triangle. Although in the semiotic triangle only the four elements are usually given which can also be found in Lyons’ representation (namely: word, form, meaning (concept), referent) it is also obvious from the above quotation from Lyons that there is always a fifth element involved too, namely the user/interpreter of the word, since the concept is to be understood as «concept associated with the form of the word in the minds of the speakers of the language».

Discussions about the nature of word meaning have been and continue to be centered around the following three questions: (1) the question most often discussed is whether or not signifying things actually takes place by virtue of the concept; in other words, whether or not the concept (in other terminology: the sense, the intension) determines the referent (in other terminology: the denotatum, the extension, the extralinguistic correlate); (2) the second question concerns the character and organization of the concept assigned or assignable to a word; finally, (3) the third question raises the problem of whether it is the concept, the referent or both together which should be considered as the meaning of a word.

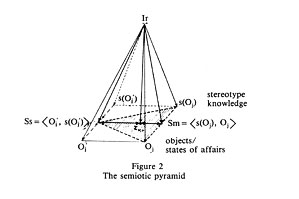

1.1.2. We replace the semiotic triangle by a semiotic pyramid (cf. Figure 2) in which we take the results achieved so far by research on the above questions into consideration552.

—288→

The analogon of the semiotic triangle in the semiotic pyramid is the triangle defined by the vertices indicated by the symbols Ss, s(Oj) and Oj. Before dealing with the components of this analogous triangle, let us have a look at the explication of the symbols of the semiotic pyramid.

The symbol Oj stands for the object/state of affairs (= correlate), to which the signifier refers. The symbol Oi stands for the object which is used as the signifier object (= the vehicle of the significans). The symbols s(Oj), and s(O’i) stand for those stereotype knowledge-systems (of laymen and/or experts) which are assigned by the users of the signifier object O’i to the object Oj (object/state of affairs) and the signifier object respectively. The symbol Ss stands for the Significans conceived as a pair consisting of the object O’i and the knowledge system s(O’i) assigned to it; similarly, the symbol Sm stands for the Significatum conceived as a pair consisting of the object/state of affairs and the knowledge system s(Oj) assigned to it. The symbol Ir stands for the Interpreter, and the symbol ∑k,o stands for the sign (= signum) conceived as the manifestation of the relation Ss-Sm. The arrows symbolize that both the significans and the significatum and the signum are (complex) objects depending on the interpreter.

—289→1.1.3. The triangle Ss-s(Oj)-Oj and the traditional semiotic triangle diverge from one another in the following ways: (a) in the semiotic pyramid both the significans and the significatum are a pair; the object O’i can fulfil the role of the significans only together with the knowledge /s(O’i)/ assigned to it by the users of this object as a semiotic object (= a vehicle of the significans); since -as the results of language philosophical research show it- the concept and its analogon in the semiot ic pyramid /s(Oj)/ do not clearly determine the referent and its analogon in the semiotic pyramid / = Oj (= the correlate)/, respectively, the meaning (in our terminology the significatum) is necessarily a pair consisting of concept and referent; (b) the signum ∑k,o in the semiotic pyramid corresponding to the element word in the semiotic triangle is in direct connection with both the Ss and the Sm, more precisely, it manifests the connection established on the basis of the knowledge system and/or the communicative activity of the interpreter(s); (c) the meaning relation in the semiotic pyramid exists between the pairs Ss and Sm (we call this relation signification relation), i.e. the signification relation is neither identical with the Ss-s(Oj) (more exactly the O’i-s(Oj)) relation generally declared to be the meaning relation by linguists, nor the Ss-Oj (more exactly O’i-Oj) relation generally declared to be the meaning relation by the logicians.

On analogy with the traditional terminology we call the Ss-s(Oj) relation the designation relation, while the relation Ss-Oj will be called the denotation relation. For naming the s(Oj)-Oj relation we have introduced the term correspondence, with respect to s(Oj) we speak about explication relations.

For simplicity’s sake and in order to express the unity of the single sign components we can use the following notation in connection with a sign:

instead of O’i (the vehicle of the

significans),

instead of O’i (the vehicle of the

significans),

instead of s(O’i) (the stereotype knowledge concerning the

vehicle),

instead of s(O’i) (the stereotype knowledge concerning the

vehicle),

instead of Ss (the

significans as a

<O’i, s(O’i)> pair),

instead of Ss (the

significans as a

<O’i, s(O’i)> pair),

instead of Oj (the correlate),

instead of Oj (the correlate),

instead of s(Oj) (the stereotype knowledge concerning the correlate),

instead of s(Oj) (the stereotype knowledge concerning the correlate),

instead of Sm (the

significatum as a <s(Oj), Oj>

pair).

instead of Sm (the

significatum as a <s(Oj), Oj>

pair).

In other words, the special quotation marks serve for indicating an elementary or complex component of a given ∑k,o553.

1.2. In the semiotic pyramid in place of the element word we use the symbol ∑k,o referring to any possible sign. The expression possible sign can be understood in two ways: (1) the symbol ∑k,o refers to a possible sign in the sense that we can imagine any kind of object as the O’i element of the semiotic pyramid, not only elements of a natural language; the subscript k refers to the class of the chosen O’i object (i.e. indicates wether the object O’i is a verbal object, a flag-movement, a picture, a not homogeneous object, etc.); the subscript o refers to the organization of the chosen O’i object (i.e. indicates whether the O’i object is a linearly or not a linearly ordered object or an object ordered according to some other arrangeing principle); (2) the symbol ∑k,o is, further, a symbol referring to any possible sign also in the sense that we can interpret an <Ss, Sm> pair of any extent and any complexity as a sign (to express it concerning verbal signs and not in terms of a precise terminology: not only words but also texts, further, not only words/texts to be understood in their direct sense but also those with a symbolic meaning).

In the lexicon of a language (= a system of signum) there can, of course, be represented only the conventionalized signification-relations concerning elementary signs -the so-called elementary systemic <Ss, Sm> pairs. The <Ss, Sm> pairs produced in the course of the communication (involved in communication situations) -and called, consequently, communicative <Ss, Sm> pairs- can be different from the systemic ones in the case of elementary signs as well.

Finally it should also be mentioned that not only objects, physical states or events can be imagined as Oj-s (i.e. as correlates) but also emotional states, either on their own or accompanying objects, physical states or events. Both with the construction of a lexicon and in the course of interpretation it is necessary to treat the question, of how to handle these emotional states: what is to be considered as systemic in connection with them -if there is anything that can be considered as systemic at all, and how to reveal the solely communicative manifestation of them.

—291→1.3. The basic operation of natural language communication is interpretation. Thus, in the present subsection we want to deal with some aspects of interpretation. These aspects are the following: the possible objects of interpretation, the possible goals of interpretation, the different types of interpretation and, finally, the main factors of meaning-constituting interpretation.

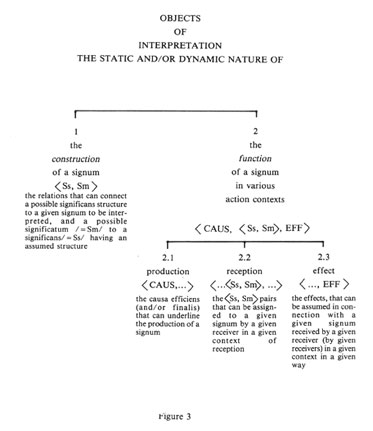

1.3.1. A global summary of the possible objects of interpretation is given in Figure 3. The two main distinctions presented in this Figure are the following: (1) the interpretation may be directed towards the relationship between the significans and the significatum i.e. the construction of a signum in general, or it may be directed towards the functional embeddedness into various contexts of a given signum; (2) the interpretation may also be directed towards the static nature of the construction and/or of the functional embeddedness (the description of what kind of relations exist (can exist) between such and such elements), or it can be directed towards the dynamic nature of the construction and/or of the functional embeddedness (the description of how the relations between such and such elements arise (can arise)).

Concerning the interpretation directed towards the static nature of the relations it is usual to speak about structural interpretation, while concerning the dynamic nature of the relations the interpretation is usually called procedural interpretation554.

Within the four main interpretation types which can be constructed by applying these two main distinctions it is possible to define a number of subtypes, many more than indicated by the differentiation in connection with the functional embedding in Figure 3. These subtypes come into existence by focusing the interpretation on different elements of the relations.

For example, the following subtypes of structural and procedural interpretation can be defined. (When enumerating the subtypes we specify the question which is to be answered by the interpretation concerned.)

—292→

A. Subtypes of structural interpretation

For 1

(a) What kind of relations can connect a possible significans structure to a given signum -assuming a knowledge and/or belief system, and the rule system of an apparatus?

(b) What kind of relations can connect a possible significatum to a significans having an assumed structure -assuming a knowledge and/or belief system, and the rule system of an apparatus?

For 2.1

(c) What kind of relations can connect a significans to an assumed significatum to be expressed (= a significandum) by a text producer with specific properties in a given context?

(d) What kind of relations can be postulated between the psychological condition and/or social position of a text producer, and a signum produced by him?

(e) What kind of relations can be postulated between the assumed intention of a text producer with specific properties concerning a given effect that is to be reached by way of communication, and a signum produced by him?

For 2.2

(f) What kind of relations can connect a possible significans structure to a given signum in a given context -assuming a knowledge and/or belief system and a rule system internalized by a receiver with specific properties?

(g) What kind of relations can connect a possible significatum to a significans having an assumed structure in a given context -assuming a knowledge and/or belief system and a rule system internalized by a receiver with specific properties?

For 2.3

(h) What kind of relations can be postulated between the reception of a signum with an assumed significans-significatum structure in a given context in a given way, and the effect (that can be) produced by this reception?

—294→B. Subtypes of procedural interpretation

For 1

(a) In what way do the knowledge and/or belief system and rules of an apparatus control the assignment of a possible significans structure to a given signum?

(b) In what way do the knowledge and/or belief system and rules of an apparatus control the assignment of a possible significatum to a significans having an assumed structure?

For 2.1

(c) In what way does a significatum to be expressed (= a significandum) control the constitution of a significans -assuming a text producer with specific properties and a given context?

(d) In what way does (can) the psychological condition and/or social position of a text producer become the causa efficiens of a given signum?

(e) In what way does the assumed intention of a text producer with specific properties concerning a given effect that is to be reached by way of communication control the production of a given signum?

For 2.2

(f) In what way does a knowledge and/or belief system and a rule system internalized by a receiver with specific properties control the assignment of a possible significans structure to a given signum in a given context?

(g) In what way does knowledge and/or belief system and a rule system internalized by a receiver with specific properties control the assignment of a possible significatum to a significans with an assumed structure in a given context?

For 2.3

(h) In what way does the reception of a signum with an assumed significans-significatum structure in a given context in a given way control the arising of an assumed effect?

It is obvious that in these interpretation subtypes the relationship/interaction among the elements concerned manifest itself in different configurations.

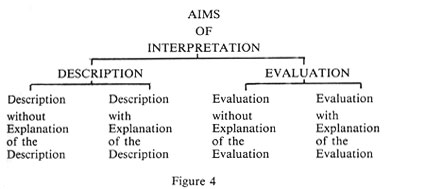

—295→1.3.2. As to the possible aims of interpretation, we can distinguish between descriptive, explanatory, and evaluative interpretation, making these distinction in such a way that each interpretation presupposes the interpretation(s) preceding it in the enumeration. It is, however, not only possible but also necessary to distinguish partly more flexible, partly more complex interpretation types. If we combine, for example, the main interpretation-types presented in Figure 4, we can achieve the following types:

(a) descriptive;

(b) descriptive with explanation of the description;

(c) descriptive and evaluative;

(d) descriptive with explanation of the description, and evaluative;

(e) descriptive, and evaluative with explanation of the evaluation;

(f) descriptive with explanation of the description, and evaluative with explanation of the evaluation.

It is easy to see that the different aims of interpretation can be combined with different objects of interpretation: thus, for example, the interpretation of all objects enumerated under point 1.3.1. (cf. A and B) can also be carried out with respect to any of the aims enumerated above.

Further variants of these interpretation types come into being if we apply different argumentation systems for the explanation process and/or different norm systems for the evaluation process. As far as the explanation —296→ is concerned, it may be the case that we can apply different argumentation systems on the same explanation level, however, it may also be the case that we can construct explanations for the same description on different levels: we can explain e.g. the dynamic nature of verbal objects by means of semiotics alone, however, we can also explain (try to explain) it by means of psychology or neurophysiology. Furthermore, it is important to ask, whether the different argumentation systems and norm systems can be evaluated on the basis of some meta-system or not, and whether these meta-systems themselves can be evaluated on the basis of a (meta-)meta system related to them, etc.

1.3.3. Finally, we also want to emphasize the basic importance of distinguishing between natural, theoretical, and automated (simulated by means of a computer) interpretation. By natural interpretation we mean that a reader/listener deals with the connection between a signum and its possible meaning, and/or with the way the given signum and/or its effect arise, and he explains and evaluates these phenomena in the natural context of reading/listening. By theoretical interpretation we mean the performance of the interpretative operations controlled by a given theory, i.e. where the interpreter has to meet specific criteria defined within the frame-work of a theory when he performs the interpretation and/or he presents the result of his interpretation. By automated interpretation we mean that the process of interpretation is automated with respect to certain aspects, i.e. the natural or theoretical interpretation is simulated with the aid of a computer with respect to certain aspects. The possible extent of simulation depends on the actual state of development of the soft- and hardware technology as well as on the actual state of knowledge concerning language and language processing.

1.3.4. The types of interpretations enumerated are either directed towards the interpretation of the construction of the signum, or they presuppose it. Thus, this type of interpretation (let us call it further on meaning-constituting interpretation) holds a central place among the interpretations.

In the meaning-constituting interpretation the following factors play a decisive role:

(1) the signum to be interpreted -as a physical object;

(2) the perceptive image of this object arising in the interpreter, and its explicit representation;

—297→(3) the prosodic (phonetic/phonological), syntactic, and formal poetic/rhetorical constitution of this perceptive image (= the constitution of the significans component of the perceived signum);

(4) the semantic, pragmatic, and non-formal poetic/rhetorical constitution of this perceptive image (= the constitution of the significatum component of the perceived signum);

(5) the assumed world-fragment manifesting itself in the perceived signum (in other words: the assumed «relatum-universe» which can be assigned to the signum to be interpreted);

(6) the interpretation model(s) (= the knowledge/hypotheses concerning state-of-affairs configurations that are acceptable to the interpreter as interpretamentum/interpretamenta) activated/reactivated by the constitution of the perceived signum and the assumed relatum universe;

(7) the interpretamentum/interpretamenta (= the interpretive state-of-affairs configuration(s)) assignable to the perceived signum in the given context of interpretation by means of the interpretation model(s)555.

—298→Some of this factors will be treated in more detail in the section 3-5 of this paper.

In this section we will be concerned with the notion verbal text, with the basic notions used in connection with the interpretation of the construction of texts, with the representation languages applied in the course of the interpretation, and with some questions of the performance of the interpretation process556.

2.1. In the first section signs in general have been considered, in this section following now solely verbal texts will be dealt with. By the term verbal we refer to a class of signs, the vehicle of which homogeneously consists of either written or sounding lexical elements. The term text is used to refer to verbal objects which, to the mind of the interpreter, in a real or assumed communication situation can be considered a connected and complete whole fulfilling a real or assumed communicative intention.

We do not consider it necessary to distinguish texts and discourses and, thus, to use the term discourse, too. The term discourse is used by some researchers to indicate text + its context, while other researchers use it to indicate spoken text. For us this distinction does not appear to be necessary, because, on one hand, we do not think that it is possible to interpret texts without taking a real or assumed communication context into consideration, on the other hand, in our opinion, the immediate object of interpretation must be in the case of both written and spoken texts their transcription. If we confine ourselves only to the interpretation of the above described homogeneous verbal objects (or verbal objects made homogeneous) these transcriptions must contain, —299→ in addition to the lexical material also, for example, the prosodic information assignable/to be assigned to this material. Prosody is not only a feature of spoken language, the interpretation of written texts is also determined by the (internal) prosody applied by the interpreter of a text.

In what follows we want to present a short explication of the terms we will use later in analyzing a text.

2.2. In connection with verbal texts we speak of their construction (cf. Figure 3). By the term construction we mean a property of a verbal text, namely the property, that it expresses a set of states of affairs of a specific configuration using verbal material of a specific constitution.

The terms construction, constitution, and configuration all indicate assumed inherent properties: constitution refers to an inherent property of verbal material, configuration refers to an inherent property of a set of states of affairs (if such a set has an inherent property at all), construction refers to an inherent property of the relation between verbal material and a set of states of affairs assignable to it in an interpretative way. The term verbal text according to the above explications serves in a narrower sense to indicate verbal material with the given constitution of a verbal object considered as a text.

The aim of the interpretation is to bring about theoretical constructs which can be considered as an optimal approximation of the assumed inherent properties from the point of view under investigation. As already mentioned in the first section, we use the terms structure and procedure making these terms more specific by appropriate prefixes, for indicating the theoretical constructs. Since we speak of assumed inherent properties, we do not exclude the possibility of approaching a property of a text by different structures/procedures (which are not necessarily compatible with each other) even if one and the same property of one and the same text is being interpreted from one and the same perspective.

2.2.1. The main terms used in connection with the analysis of constitution -again to indicate properties as being considered inherent- are the following: texture and composition on one hand, and continuity (connexity and cohesion) and completeness on the other hand.

By the term texture we mean the pattern to be found in the constitution of the text which arises from the repetition/parallelism of parts of signs, of elementary signs, of complex signs, or of the categories assigned to them. Since the disclosure of the recurring signs and/or categories —300→ in the analysis of the texture depends on the lay or scientific theory applied, the textural structure constructed as an approximation of the texture is always a structure depending on the theory applied.

By the term composition we mean the hierarchical architecture of the text constitution. In other words, we mean that specific property of text constitution, that it comes into being from independent elementary constituents through first grade, seconde grade, etc. composition units of various complexity. Since the definition of independent elementary constituents as well as that of composition units of different grades depends on the lay or scientific theory applied, the compositional structure constructed as an approximation of the composition is also always a structure depending on the theory applied.

Using a metaphorical expression, texture is a horizontal property, composition is a vertical property of constitution.

The term continuity refers that specific property of text constitution, that it has no single micro or macro composition unit which is not connected to at least one other micro or macro composition unit in a textural and/or compositional way. Continuity does not require that adjecent micro or macro units be connected, it is, however, a requirement that there be no island in the constitution.

By the term connexity we mean that form of continuity which is manifest in the constitution of the significans component of the text.

The term cohesion, on the other hand, serves to indicate that form of continuity which is manifest in the constitution of the significatum component of the text.

The term completeness refers to the functioning-as-a-whole property of the constitution of the text investigated from a certain point of view, with respect to a certain specific expectation. The expectation and, as a consequence, also the completeness is dependent on the lay or scientific theory applied557.

The terms texture and composition as well as continuity (connexity and cohesion) and completeness can be used in all possible combinations; —301→ thus we can speak of the textural continuity and completeness of constitution as well as of compositional continuity and completeness of constitution, and we can also specify the properties connexity and cohesion similarly.

2.2.2. Although in the present paper we want to discuss aspects of text constitution, we also want to touch upon the -non constitution specific- terms used in connection with the interpretation of text construction.

In order to be able to interpret a text, we first have to (re-)construct the world-fragment (in other word: the relatum universe) which is implicitly manifest in the text to be interpreted. This relatum universe renders it possible to construct interpretation models, with the aid of which we can assign an interpretation/interpretations, in our terminology an interpretamentum/interpretamenta, to the text to be interpreted. (Cf. 1.3.4 (5)-(7).) On this basis we call a text interpretable with respect to an interpreter (with respect to the knowledge/belief and rule systems internalized and used by him in the context of the interpretation), if it is possible for him to assign at least one interpretamentum to the text to be interpreted.

Both the relatum universe, the models, and the interpretamenta are representations of-states-of-affairs configurations. In connection with these configurations we use the terms constringency and integrity as indicators of assumed inherent properties of the configurations.

The term constringency refers to that specific property of a configuration, that its elements are connected to one single continuum by relations relevant for the interpreter, where the term continuum is understood in the sense in which continuity is explicated above.

The term integrity is an analogue of the term completeness, expressing that the state-of-affairs configuration in question is an entirety meeting the expectations of the interpreter.

We use the term coherence in connection with the relation between the relatum universe and the interpretamentum, and we distinguish explicitly coherent texts and latently coherent texts. A text is called explicitly coherent if it contains the representation of all the states of affairs required by the interpretamentum. A text is called latently coherent if the text does not contain the representation of all the states of affairs required by the interpretamentum, however, the representations of the —302→ missing states of affairs can be derived from those given in the text in a motivatable way.

Since the interpretamenta depend on the interpretation process, and since motivatability is a category specific for the interpreters, one and the same text can be qualified as explicitly coherent, latently coherent, or even incoherent, depending on different interpretation processes and/or different interpreters with reference to which the text has been qualified558.

2.2.3. To conclude the explication of the terms we would like to emphasize that to our mind (a) the terms textuality, interpretability, connexity, cohesion, and coherence are to be used as terms referring to assumed independent inherent properties of the objects to be interpreted, and (b) it is expedient to operate with the negative pairs of these terms as well.

2.3. To interpret and describe the text construction/text constitution in an explicit way we need different (representation) languages: a transcription language, canonical languages which are independent of the structure of natural languages, as well as meta-languages concerning the natural language, the transcription languages, and the canonical languages.

A transcription language is necessary for producing the transcripts representing the immediate object of interpretation, which have to supply optimal information as to the perceptive image of the text as a physical object. As has already been mentioned, transcripts are needed not only in the case of oral texts, but also when written texts are to be interpreted. (The nature and amount of information required to be included in the transcripts always depends on the actual interpretation situation.) Transcription languages can be elaborated e.g. on the basis of the principles specified by the International Phonetic Association, however, they can also be constructed on the grounds of some other requirements.

While the transcription languages serve to transcribe the vehicle of the significans (and to complete it by accessory information), the canonical languages are those languages into which we translate the text to be interpreted. A canonical text can be considered as the representation —303→ of the deep structure of the text to be interpreted -using the term deep structure in connection with both the significans and the significatum. The canonical texts are representations which are in general independent of a linear or any other kind of arrangement of natural language texts, and they render it possible to represent optimally the knowledge (involved in the given context) about the object/state-of-affairs configuration signified by the significans559.

The metalanguages are those terminologies by means of whose elements we name the expressions/units of the natural languages, of the transcriptions and of the canonical languages. Thus, the system of categories used by the grammar of a given natural language is a metalanguage.

When a procedural analysis is to be carried out, we also need a metalanguage which names the steps of the procedural operations.

These languages should be introduced in the frame-work of the theory to be used in the interpretation process in a consistent and with each other compatible way.

2.4. In section 1.3.4. we have enumerated those objects which play a decisive role in the interpretation process. As to the performance of the interpretation process itself, we want to make the following remarks:

-the discussion of the dynamic aspects of the interpretation process requires the analysis of what size language units have to have when the interpretation begins to operate -and in what way it operates- with all of the objects (1)-(7) enumerated in 1.3.4. (One can hardly imagine an interpretation process, in which we could construct the objects (1)-(7) in the order of the enumeration with respect to the complete text.);

-even if connexity is not a condition of cohesion, it certainly influences its analysis;

-even if cohesion is not a condition of coherence, it certainly influences whether a text will be qualified as coherent or not coherent, since it influences the construction of both the relatum universe and the models;

—304→-in the course of the interpretation the interpreter can change his mind concerning both the connexity and the cohesion of the text. (The disambiguation of individual composition units e.g. can have both semantic and syntactic consequences as to the results or the first interpretation; disambiguation may require the repetition of the whole interpretation process.);

-as a consequence of what has been said above, the final description of the connexity and cohesion of a text within an interpretation process can only be carried out after having completed the interpretation process.

3.0. In this section we want to demonstrate some aspects of text constitution in connection with the analysis of a text. This text is Chapter XXIII of Le Petit Prince560.

Since we have presented neither a transcription language nor any canonical languages, we will only deal with aspects which can be analyzed with respect to the surface manifestation of the printed text and we will use traditional grammatical categories.

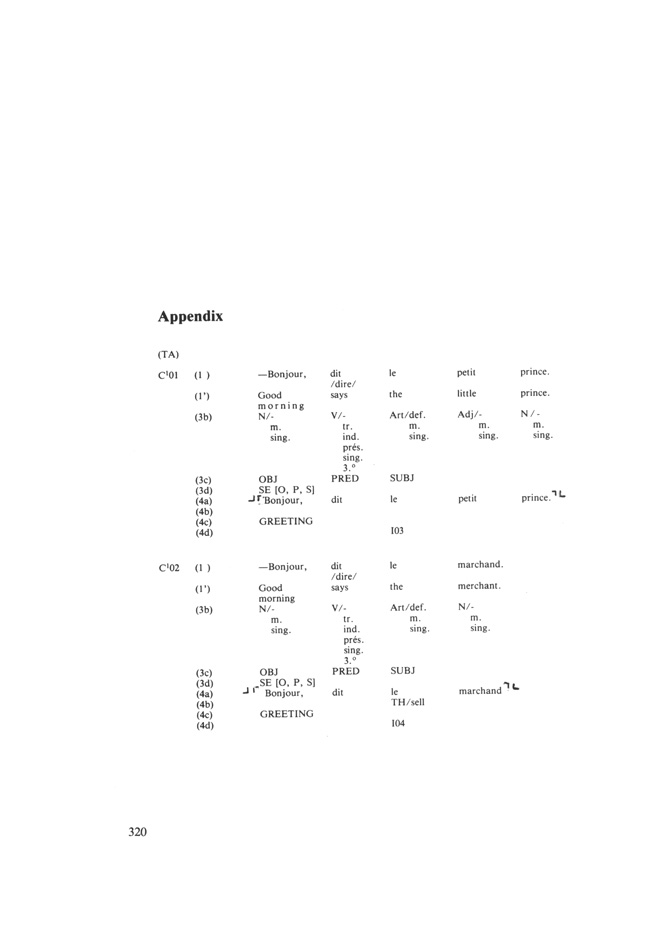

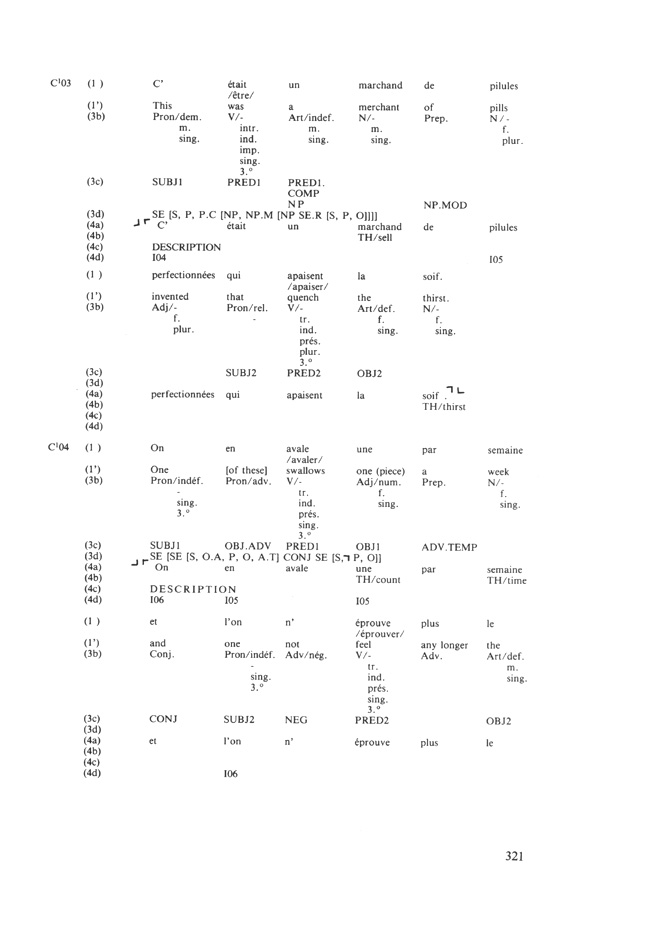

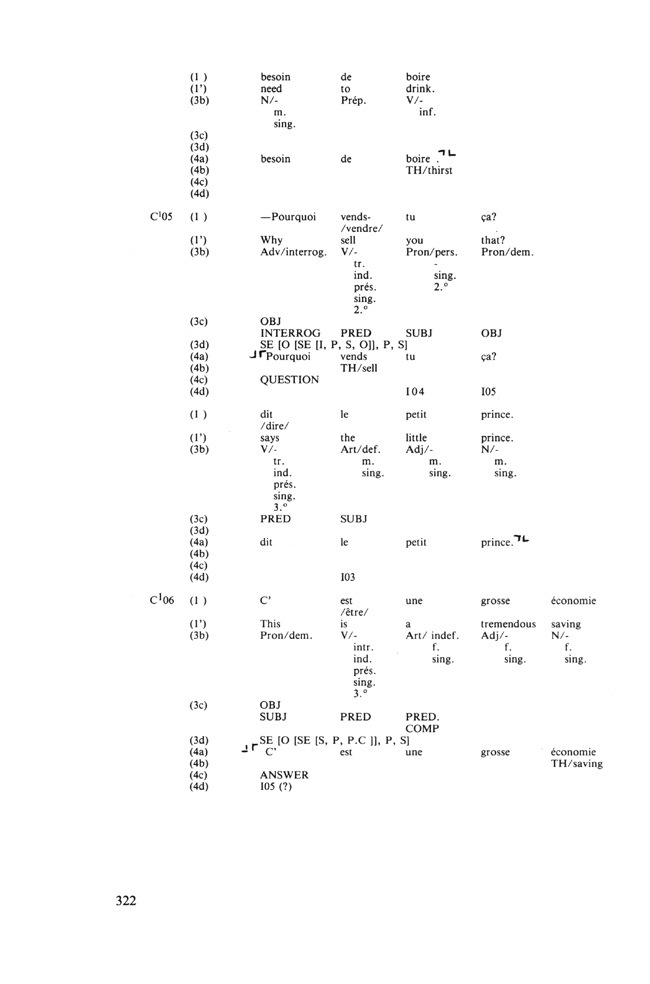

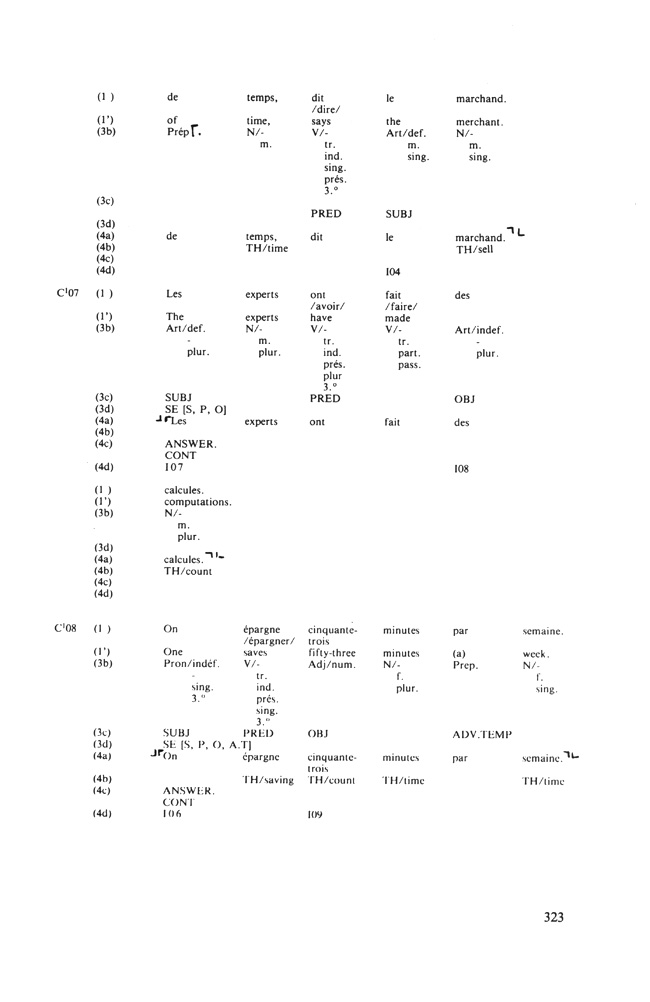

(T) represents the text to be analyzed and its literary English translation. (TA) represents a partial syntactic and semantic analysis of the original text (cf. Appendix).

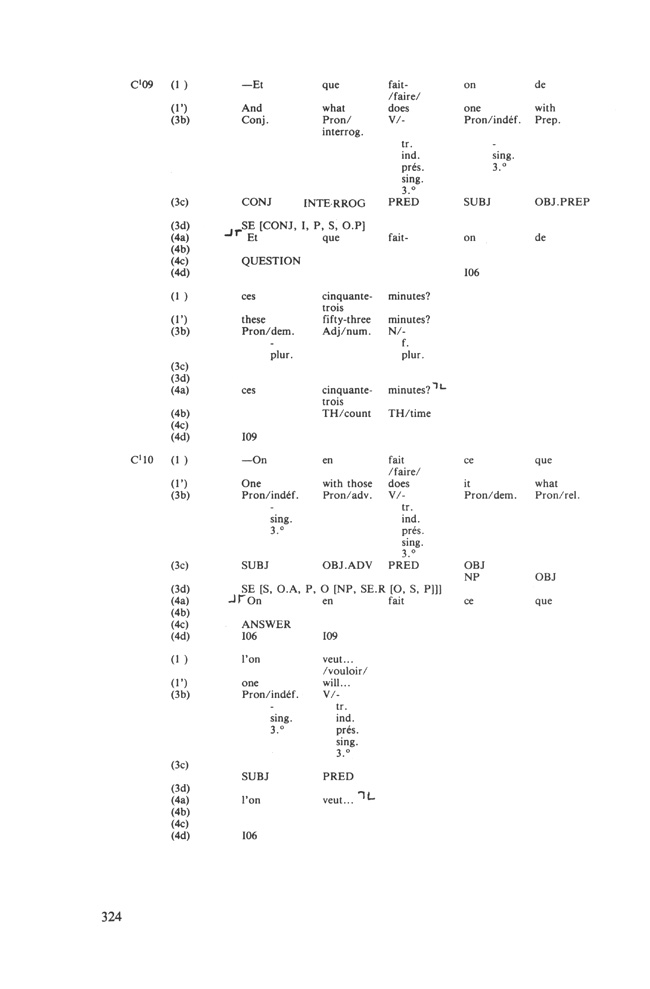

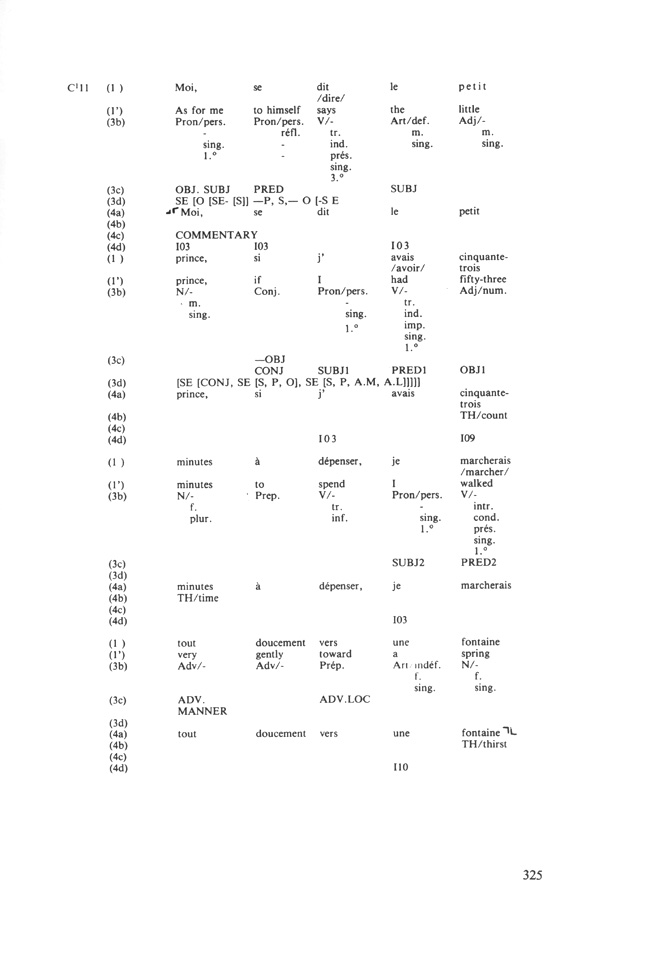

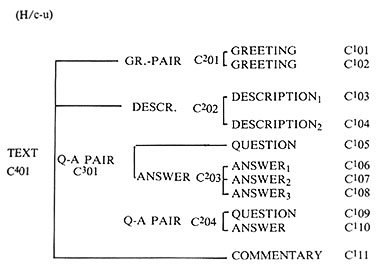

Some technical remarks on (TA): the symbol C101 indicates the first / = 01 / first-grade

composition-unit / = C1 /. The other C

symbols are to be read accordingly; the sectors (1), (3) and (4) correspond to

interpretation factors with identical serial numbers given in section 1.3.4.

(the reason why (2) is missing is that, for simplicity’s sake, we have

omitted here an explicit representation of the perceptive image); (1’)

represents the literal English translation assigned to (1); since we have not

represented the perceptive image, we did not deal with the role prosody plays

in the constitution either, and that is why we began to indicate the

sub-sectors of sector (3) by (3b); in (3b) we have operated with parts

—305→

of speech and morphological categories applied in the dictionary

Petit Robert; since the abbreviations of

these categories correspond almost totally to the English abbreviations we do

not find it necessary to explicate them here; in (3c) we operate with

traditional sentence grammatical categories; (3d) represents the

sentence-grammatical structure of the individual composition-units where the

beginning letters of the sentence-grammatical categories used in (3c) have been

applied as symbols;

SE stands for

sentence,

SE.R stands for

relative clause; (4a) is supposed to contain

the sense representation of the individual words, we refer to them in (TA) only

by putting the first-grade composition-unit in question into the special

brackets

indicating sense; (4b) represents so-called thesauristic /TH/ relations (sell, thirst, saving, time); (4c) displays the communicative

function of the individual first-grade and second-grade composition-units (GREETING, QUESTION, ANSWER, etc.); finally, (4d) represents

the coreference indices referring to the objects named in (T).

indicating sense; (4b) represents so-called thesauristic /TH/ relations (sell, thirst, saving, time); (4c) displays the communicative

function of the individual first-grade and second-grade composition-units (GREETING, QUESTION, ANSWER, etc.); finally, (4d) represents

the coreference indices referring to the objects named in (T).

(T)

| XXIII | XXIII |

| 25 -Bonjour, dit le petit prince. | -Good morning, said the tittle prince. |

| -Bonjour, dit le marchand. | -Good morning, said the merchant. |

| C’était un marchand de pilules perfectionnées qui apaisent la soif. On en avale une par semaine et l’on n’éprouve plus le besoin de boire. | This was the merchant who sold pills that had been invented to quench thirst. You need only swallow one pill a week, and you would feel no need of anything to drink. |

| 30 -Pourquoi vends-tu ça? dit le petit prince. | -Why are you selling those? asked the little prince |

| -C’est une grosse économie de temps, dit le marchand. Les experts ont fait des calculs. On épargne cinquante-trois minutes par semaine. | -Because they save a tremendous amount of time, said the merchant. Computations have been made by experts. With these pills, you save fifty-three minutes in every week. |

| -Et que fait-on de ces cinquante-trois minutes? | -Anything you like... |

| 35 -On en fait ce que l’on veut... | -And what do I do with those fifty-three minutes? |

| Moi, se dit le petit prince, si j’avais cinquante-trois minutes à dépenser, je marcherais tout doucement vers une fontaine... | As for me, said the little prince to himself, if I had fifty-three minutes to spend as I liked, I should walk at my leisure toward a spring of fresh water. |

3.1. The notion of connexity has been explicated in section 2.2.1. in the following way: by the term connexity we mean that form of continuity which is manifest in the constitution of the significans component of the text. This implies that the description of connexity happens on the basis of the knowledge we have about the significans. From among the possible classes of this knowledge (TA) contains only a few. We want to discuss briefly the connexity that can be explained on the basis of these classes.

3.1.1. Let us see first some possible constituting elements of textural connexity.

Line (1) of (TA) contains the vehicle of the significans, more exactly its graphic vehicle. In this graphic vehicle the following repetitions occur (cf. the matrix M(1))561.

M(1)

| 01 | 02 | 03 | 04 | 05 | 06 | 07 | 08 | 09 | 10 | 11 | |

| Bonjour | + | + | |||||||||

| dit | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||

| le petit prince | + | + | + | ||||||||

| le marchand | + | + | + | ||||||||

| semaine | + | + | |||||||||

| cinquante trois minutes | + | + | + | ||||||||

| on | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| fait | + | + | + | ||||||||

| — | + | + | + | + | + | + |

On the basis of the parts of speech categories the following repetitions can be shown in the sector of the syntactic categories (cf. M(3b)).

M (3b)

| 01 | 02 | 03 | 04 | 05 | 06 | 07 | 08 | 09 | 10 | 11 | |

| N/sing. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||

| N/plur. | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||

| V/intr. | + | + | + | ||||||||

| V/tr. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| V/prés. | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| V/imp. | + | + |

In the sector (3b) the signs -in the category symbols N/-, V/- and Adj/- are dummies for subcategories. In a full analysis in these places those categories of the syntactic subclasses will appear which the grammar of the given languages uses. Similar matrices can be constructed on the basis of the categories presented in (3c) and (3d).

Sector (3) does not contain all possible category classes. If we operate, for example, with a syntax which also assigns to the name/description of the objects/individuals the role they fulfill syntactico-semantically in the composition unit in question, we can set up on this basis the matrix of argument-role indicators of the text to be analyzed.

It is easy to see that in a formal respect matrix M(1) or M(3b) already in themselves guarantee the textural connexity of (T) by means of the elements/categories contained in them. However, with respect to the content constitution of the text, with prose texts this formal connexity is in itself not relevant. From among the above factors, the most relevant for content constitution of (T) is the line V/prés. and V/imp. of M(3b), which directly contributes to the interpretation of the chronological net of the text. However, as far as the formal constitution of the text is concerned, for a formal stylistic analysis, connexity revealed by means of any of the category-classes can be relevant. (This statement holds even more for the prosodic structure assignable to the text, since the prosodic rhythm of the text, for example, can only be described with reference to it.)

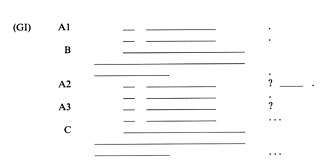

3.1.2. In connection with compositional connexity we only want to add one remark. The graphic image / = GI/of (T) can be represented schematically as follows (cf. (GI)).

We are convinced that the way in which the graphic image of (T) has been composed (A1, B, A2, A3, C), also supplies compositionally interpretable information for those who do not understand French.

3.1.3. The notion completeness cannot be applied as unambiguously or convincing in connection with the connexity of prose text as it can in connection with poems. Whether or not a poem shows the form of a sonnet, for example, can unambiguously be stated, even if we do not understand the text itself. With respect to prose texts we do not know a canon which could be applied formally in a similar way.

—308→

3.1.4. The factors discussed in 3.1.1. and 3.1.2. are the carriers of the so-called intratextual connexity. Besides intratextual connexity we can also speak of intratextual connexity.

We could, for example, also establish the M(1) and M(3b) matrices and the schemes of the graphic images with respect to the whole text of Le Petit Prince. In the matrix M(1) thus yielded a frequently recurring element would be not only the expression le petit prince but also the expression Bonjour, dit le petit prince. We also would obtain many graphic images which are analogous to (GI). The explication of these would enable us to draw much further reaching conclusions than it would be the case with intratextual matrices.

3.2. The notion of cohesion has been explicated in section 2.2.1 in the following way: the term cohesion serves to indicate that form of continuity which is manifest in the constitution of the significatum component of the text.

The significatum consists of two components -as we have seen in the first section-: the object(s)/state(s)-of-affairs (referred to as correlatum) and the stereotyp knowledge about it/them (referred to as sense). With respect to texts, the sense component itself is complex: one of its subcomponent is the direct verbal content of the text (in our terminology: dictum), the other subcomponent is a world fragment (a special states-of-affairs configuration), which the interpret assumes implicitly to —309→ manifest itself in the dictum. (In our terminology the manifestation of this world-fragment is called relatum)562.

If, for example, we read the text I remember that two years ago Peter was very ill, we are directly confronted with the dictum, and it is easy to understand, what the text wants to say. However, behind this dictum one can assume different world fragments (different text worlds): it is possible that (a) the person called Peter was in fact very ill two years ago, and the speaker (really) remembers that at the time of the communication; it is also possible that (b) the person called Peter was not ill two years ago, the speaker, however, remembers at the time of the communication that he was; finally, it can also be the case that (c) the person called Peter was not ill two years ago, the speaker does not remember at the time of the communication that Peter was ill, however, ha says at the time of the communication that he remembers nevertheless.

The representation of the relatum requires on one hand the assignment a canonical propositional-representation (which also contains the so-called world-constitutive propositions) to the text to be interpreted, on the other hand, it requires the assignment of that information to the propositional representation, on the basis of which it can be made clear which world fragment is assumed to be manifest in the dictum. (In connection with the above example, whether the interpreter assumes case (a), (b), or (c) to be true).

Since we did not want to treat the aspects concerning the relatum in detail in this contribution, we will leave these aspects out of consideration when discussing cohesion.

The (TA) represents on one hand some information concerning the dictum (cf. (4a)-(4c)), and on the other hand the reference (coreference) indices referring to the objects of the correlate. In our analysis we rely first of all upon this type of information.

3.2.1. The carriers of textural cohesion can be classified into two main classes: the class of thesauristic relations and the class of substitution relations.

—310→We call thesauristic relations those relations which exist between the sense representations assigned to individual words of the text. These sense representations are not contained in the (TA), line (4a) of (TA) only symbolizes them formally. We think, however, that it is easy to see that the thematic assignments represented in (4b) can be performed on the basis of the sense representations. The thematic assignments and the repetitions arising in them are systematically represented by the matrix M(TH). On the basis of this matrix we can say that the text (T) is not continuous, its first-grade composition-units no. 1. and no. 10. constitute islands.

M(TH)

| sell | thirst | saving | count | time | |

| 01 | |||||

| 02 | marchand | ||||

| 03 | marchand | soif | |||

| 04 | boir | une | semaine | ||

| 05 | vends | ||||

| 06 | marchand | économie | temps | ||

| 07 | calcules | ||||

| 08 | épargne | cinquante-trois | minutes semaine | ||

| 09 | cinquante-trois | minutes | |||

| 10 | |||||

| 11 | fontaine | cinquante-trois | minutes |

We interpret the so-called substitution relations in a way different from the usual way of interpreting it in literature: we do not speak of replacing a nominal phrase by other phrases (in general by pronomina), we speak rather of replacing the reference indices by different kinds of nominal phrases. This interpretation, which we do not wish to discuss in detail here, allows us to avoid many of the difficulties arising in connection with the substitution theories presented until now563.

The reference indices (which might also be called co-reference indices) are contained, as already pointed out above, in line (4d) of (TA), and the relation between the reference indices and their substituents are systematically presented in matrix M(I). With reference to this matrix —311→ we can say that the first-grade composition-unit 07 in text (T) constitutes an island. The island character of this composition unit ceases however, if we consider the whole composition unit CI08 as a manifestation (substituent) of the reference index I08564.

3.2.2. Compositional cohesion has an aspect depending rather on the state-of-affairs configuration, and an aspect depending rather on the verbal material.

The aspect depending rather on the state-of-affairs configuration is specific to the kind of text: the states of affairs are arranged in a different way if performed/described in a prose text, in an argumentative text, in a dialogue, or in a monologue, etc. The cohesion of the text (T) depending on the state-of-affairs configuration can be described in a way which is homomorphous to the structure presented in (GI) (cf. (C/s-c)).

| (C/s-c) | GREETING |

| GREETING | |

| DESCRIPTION | |

| QUESTION | |

| ANSWER | |

| QUESTION | |

| ANSWER | |

| COMMENTARY |

These pieces of information are found in line (4c) of (TA). The connection of the units of (C/s-c) with the compositional hierarchy of (T) is shown by the graph (H/c-u). This graph demonstrates that text (T) is a fourth-grade composition-unit.

As to the aspect depending on the verbal material, we can speak of the cohesion of the linear composition of the verbal units manifesting the state of affairs/state-of-affairs configurations.

The main questions concerning the cohesion of the linear composition are the following:

—312→M(I)

| I03 | I04 | I05 | I06 | I07 | I08 | I09 | I10 | |

| 01 | le petit

prince | |||||||

| 02 | le

marchand | |||||||

| 03 | c’ | pilules | ||||||

| 04 | en une | on l’on | ||||||

| 05 | le petit prince | tu | ça | |||||

| 06 | le marchand | c’ | ||||||

| 07 | les experts | des calcules | ||||||

| 08 | on | /C108/ | cinquante -trois minutes | |||||

| 09 | on | ces cinquante -trois minutes | ||||||

| 10 | on

l’on | en | ||||||

| 11 | mois se le petit prince j’ je | cinquante -trois minutes | une fontaine |

(a) which elements belong to the complete sets of possible linear arrangements of the constituents within the individual nominal, verbal, etc. phrases, and what is the relation between these sets and the linear arrangements realized in the phrases to be interpreted;

(b) which elements belong to the complete sets of possible linear arrangements of the immediate constituents within the elementary first-grade composition-units, and what is the relation between these sets and the linear arrangements realized in the elementary first-grade composition-units to be interpreted;

(c) which elements belong to the complete sets of possible linear arrangements of the immediate constituents within the complex first-grade composition-units, and what is the relation between these sets and the linear arrangements realized in the complex first-grade composition-units to be interpreted;

—313→

(d) which elements belong to the complete sets of possible linear arrangements of the constituents within the second-grade composition-units, and what is the relation between these sets and the linear arrangements realized in the second-grade composition-units to be interpreted; etc.

We do not find any example in (T) to discuss (a); for (b) we can consider the immediate constituents of every first-grade composition-units; the first-grade composition-unit of C111 can be an example for (c), in which we should analyse the set of the possible linear arrangements of the immediate constituents moi, se dit le petit prince, si j’avais cinquante-trois minutes à dépenser, and je marcherais tout doucement vers une fontaine...; the second-grade composition-unit C203 can be an example for (d), in which we should analyse the set of the possible linear arrangements of C106, C107, C108. An adequate description of the —314→ linear compositional cohesion of (T) requires to perform the types of analyses enumerated above. However, we will have to abstain from performing these analyses here.

3.2.3. It is possible to apply the notion completeness also to cohesion (especially to compositional cohesion). The question to be investigated here is, why we believe (T) to be complete if we believe it to be complete, and whether one could leave out one (or some) of its composition units without causing to believe that (T) is not complete any longer.

An interpreter believes (T) to be complete with respect to compositional cohesion, if the description of the state-of-affairs configuration manifest in it meets, according to his experience, the usual expectation concerning complete descriptions. We want to emphasize that not the individual states-of-affairs and the expectations concerning them are meant here. To operate with these is a task of model building and of constructing interpretamenta. What is meant here is the expectation concerning the description itself.

The expectation pattern which is met by (T) can be formulated in a general way as follows:

A narrator tells the meeting and the short dialogue of two persons:

-A and B greet each other / = GREETING PAIR/;

-Since the narrator assumes that B is unknown to the reader/listener, he briefly presents B /DESCRIPTION/;

-A asks B, why he is doing what he is doing; B answers the question / = QUESTION-ANSWER PAIR/;

-A is not fully satisfied by the answer/explanation of B, thus he puts another question; B answers this question, too / = QUESTION-ANSWER PAIR/;

-for A the answer of B (the fact involved in the answer) appears strange/ununderstandable, thus he gives own view about it / = COMMENTARY/.

Since this expectation pattern can be considered as stereotype, and since (T) meets this pattern, we are convinced that most interpreters will regard (T) as being complete with respect to compositional cohesion.

We will leave it to the reader to investigate the question, whether one (or some) of the composition units of (T) could be left out, and if so, which one(s).

—315→3.2.4. It is expedient also with respect to cohesion, to speak about intratextual and intertextual cohesion.

Some remarks concerning intertextual cohesion:

The elements belonging to the thematic group thirst play a relevant role in the whole text of Le Petit Prince, cf., for example, the chapters II, VII, XXII, XXIV, XXV, and XXVI. In chapter XXVI the last constituent of C111 returns almost word by word: et je serais heureux, moi aussi, si je pouvais marcher tout doucement vers une fontaine! (It would also be interesting to analyze the symbolic meaning of the elements belonging to this thematic group.)

Also the elements belonging to the thematic group count are relevant, cf., for example, the chapters I, II, IV, VII, XIII, XVI, XVII, XVIII, and XXII. The fetishism of numbers appears to be one of the most characteristic properties of men both for the narrator and for the Little Prince.

However, we also find intertextual relations concerning the compositional cohesion: consider, for example, the fact that the compositional set-up of many other chapters is similar to that one analysed above, and the fact that the basic compositional principle of the whole text is to present the views of the Little Prince in form of dialogues.

3.3. Though in the present paper we want to discuss primarily the aspects of text constitution, we also want to briefly touch upon the last three factors of meaning-constituting interpretation (cf. 1.3.4. (5)-(7)) with reference to the here analysed text (T).

The relatum universe assignable to the text (T) consists of the world of the narrator, the merchant, the experts, men (in general), and the Little Prince. The only common event in these worlds is thirst and the attitude to how to quench it; the relation between these worlds is determined by the way the persons constituting the individual worlds approach the way the persons constituting the other worlds approach thirst and how to quench it. On the basis of (T) it appears that it is not good to waste time on drinking, the experts compute how much time could be saved if one did not need to drinke, the merchant finds that saving time is important and sells pills which enable saving time, the Little Prince, however, does not understand this, he would spend the saved time for walking towards a spring.

—316→On the basis of this relatum universe the interpreter constructs his own interpretation model(s). Without going into details let us assume that the interpreter can easily construct a fictitious world in which everything happens (because it can happen) in the way as described in the text (T).

Since the interpreting model and the relatum universe which can be assigned to the text to be interpreted are compatible with each other, the model can be accepted without any modification as an interpretamentum assignable to the text (T)565.

As a consequence of compatibility, we can regard text (T) -with reference to the above outlined model and interpretamentum- as being explicitly coherent.

Two further remarks to conclude: (1) it seldom happens that the interpretation process is as free of problems concerning the factors (5)-(7) as it is the case here. In most cases it is necessary to explicitly complement the text to be interpreted by conclusions that can be drawn from the text in order that the interpretation model can be constructed and can be compared with the relatum universe at all; (2) we have dealt only with the so-called direct meaning of (T). The real meaning of (T) is, however, a symbolic meaning, the treatment of which would exceed both our goal and the frames of our study.

In our present paper we have discussed questions of the static and dynamic interpretation of text constitution. Our primary aim was to present an outline of the spectrum of these factors which (can) contribute to connexity and cohesion of texts. We are convinced that these factors can only be investigated adequately in the frame-work of an all-embracing theory, and we are also convinced that textological research leads sooner or later to the establishment of such a theoretical framework.

To conclude our study we would like briefly to outline four groups of tasks which we consider to be central for textological research at present:

—317→(1) Relying upon the experiences of textological research until now, it seems to be necessary to examine again, which are the basic questions of establishing a flexible text typology (flexible with respect to a number of aspects to be considered). We have also to investigate the question, whether conversation analysis and the analysis of written texts require different methods, and if they do, in what respect these methods differ from each other; then we have to investigate, with which categories an optimal transcription language has to operate when transcripts are to be supplied for different types of conversations and written texts.

(2) Both within the single disciplines dealing with texts and in the various contexts of interdisciplinary cooperation it is necessary to investigate which are the basic questions of establishing an integrative textological frame-work. In this investigation, on one hand, the questions primarily concerning the verbal material of texts have to be critically scrutinized again, on the other hand, the questions of the relationship between verbal constitution and text meaning. In the course of striving for integration one has to reinterpret the results of Russian Formalism and those of French Structuralism as well as the results of grammatical and of hermeneutic research -just to mention four directions which cannot be said to be convergent!

(3) Also the questions of possibilities and limits of structural and procedural analysis and of their interrelation have to be investigated. In connection with procedural analysis, special stress has to be laid on the differences between the methodological problems of real time procedural analysis (e.g. that one performed with a conversation simultaneously) and those of procedural analysis with no time restriction (e.g. the procedural analysis of a written text which does not simulate a continuous real-time reading).

(4) A considerable number of pilot studies ought to be done in order to investigate the interpretation types (and to explicitely simulate them as far as possible) which we have enumerated in point 1.3.1.

A research field of the complexity of textology requires a more extended cooperation than the cooperation trends between the different schools in the individual disciplines and even between different disciplines could become until now.

—318→

ALLÉN, S. (ed.) (1982), Text Processing. Text Analysis and Generation, Text Typology and Attribution. Proceedings of Nobel Symposium 51, Stockholm, Almqvist & Wiksell International.

BALLMER, Th. (ed.) (1985), Linguistic Dynamics. Discourse, Procedures and Evolution (= Research in Text Theory 9), Berlin-New York, W. de Gruyter.

BROWN, G. and G. YULE (1983), Discourse Analysis (= Cambridge Textbooks in Linguistics), Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

CONTE, M.-E. (ed.) (1986), Kontinuität und Diskontinuität in Texten und Sachverhaltskonfigurationen. Diskussion über Konnexität, Kohäsion und Kohärenz (= Papers in Textlinguistics 50), Hamburg, Buske.

EIKMEYER, H.-J. (1983), «Procedural analysis of discourse», in: Petöfi (ed.) (1983a), 11-37.

GÜLICH, E. and W. RAIBLE (1977), Linguistische Textmodelle, München, Fink.

HATAKEYAMA, K., J. S. PETÖFI, and E. SÖZER (1984a), «Text, connexity, cohesion, coherence», in: Sözer (ed.) (1984), 36-105. (In German version in: Conte (ed.) (1986); in French version as Documents de Travail et prépublications A/132-134, Università di Urbino, Italia.)

— (1984b), «Nachtrag zu “Text, Konnexität, Kohäsion, Koherenz”», in: Conte (ed.) (1986).

— (1984c), «Konnexität, Kohäsion und Sprachstruktur. Textanalyse», in: Conte (ed.) (1986).

HEYDRICH, W. and J. S. PETÖFI (1983), «A text-theoretical account of questions of lexical structure», Quaderni di Semantica IV, 120-127, 294-311.

HEYDRICH, W. and J. S. PETÖFI (eds.) (1984), Aspekte der Konnexität und Kohärenz von Texten (= Papers in Textlinguistics 51), Hamburg, Buske.

NEUBAUER, F. (ed.) (1983), Coherence in Natural-Language Texts (= Papers in Textlinguistics 38), Hamburg, Buske.

PETÖFI, J. S. (1982a), «Representation languages and their function in text interpretation», in: Allén (ed.) (1982), 85-122.

— (1982b), «Meaning, text interpretation, pragmatic-semantic text classes», in: Rieser (ed.) (1982), 453-491.

—319→— (1983a), «Aufbau und Prozess, Struktur und Prozedur. Einige Grundfragen der prozeduralen Modelle des Sprachsystems und der natürlich-sprachlichen Kommunikation», in: Petöfi (ed.) (1983b), 310-321.

— (1983b), «Text, signification, models, and correlates. Some aspects of text comprehension and text interpretation», in: Rickheit and Bock (eds.) (1983), 266-298.

— (1984), «Ausdrucks-Funktionen, Sätze, kommunikative Akte, Texte (Aspekte der Bedeutung und ihre Thematisierung im Rahmen einer Texttheorie)», in: Rothkegel and Sandig (eds.) (1984), 26-50.

PETÖFI, J. S. (ed.) (1983a), Methodological Aspects of Discourse Processing (= Text 3-1), Berlin-New York-Amsterdam, Mouton.

— (1983b), Texte und Sachverhalte. Aspekte der Wort-und Textbedeutung (= Papers in Textlinguistics 42), Hamburg, Buske.

PETÖFI, J. S. and E. SÖZER (eds.) (1983), Micro and Macro Connexity of Texts (= Papers in Textlinguistics 45), Hamburg, Buske.

PUTNAM, H. (1975), «The Meaning of “Meaning”», Mind, Language and Reality. Philosophical Papers. Vol. II., Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 215-271.

— (1978), «Meaning, reference and stereotypes», in: Meaning and Translation. Philosophical and Linguistic Approaches, ed. by Guenthner, F. and M. Guenthner-Reutter, London, Druckworth, 61-81.

RAIBLE, W. (1984), «Phänomenologische Textwissenschaft. Zum Beitrag von K. Hatakeyama, J. S. Petöfi und E. Sözer (Text, Konnexität, Kohäsion, Kohärenz)», in: Conte (ed.) (1986).

RICKHEIT, G. and M. BOCK (eds.) (1983), Psycholinguistic Studies in Language Processing (= Research in Text Theory 7), Berlin-New York, W. de Gruyter.

RIEGER, B. (ed.) (1984), Dynamik in der Bedeutungsskonstitution (= Papers in Textlinguistics 46), Hamburg, Buske.

RIESER, H. (ed.) (1982), Semantics of Fiction (= Poetics 11), Amsterdam, North-Holland.

ROTHKEGEL, A. and B. SANDIG (eds.) (1984), Text - Textsorten - Semantik. Linguistische Modelle und maschinelle Verfahren (= Papers in Textlinguistics 52), Hamburg, Buske.

SÖZER, E. (ed.) (1984), Text Connexity, Text Coherence. Aspects, Methods, Results (= Papers in Textlinguistics 49), Hamburg, Buske.

—320→