—262→

Department of Languages, Literatures, and Cultures

University of South Carolina

Columbia, S.C. 29208

et-aylward@sc.edu

As generations of Hollywood screen writers have learned to their chagrin, turning out a successful sequel to a blockbuster hit can be a tricky piece of work, especially if the original author is not involved in the production of the follow-up. But anyone familiar with the history of Spanish literature already knows how long the odds are against the critical success of such an effort. Celestina inspired many ambitious spin-offs, none of which came anywhere close to enjoying Fernando de Rojas's critical and commercial success of 1499. Similar unsuccessful imitations include Juan Martí's 1602 attempt to benefit from the phenomenal sales of Mateo Alemán's Guzmán de Alfarache (1599) and Juan de Luna's 1620 tepid continuation of the classic picaresque biography, Lazarillo de Tormes (1554). Gaspar Gil Polo's pastoral Diana enamorada (1564), a critically acclaimed sequel to Jorge de Montemayor's Siete libros de la Diana (ca. 1559), was a notable exception to the rule. Alonso Fernández de Avellaneda's 1614 unauthorized and spurious continuation of Miguel de Cervantes' Don Quijote is perhaps the most notorious of Spanish literary sequels, relegated to the literary dustbin over the years, largely because an indignant and irate Cervantes went to great lengths to trash Avellaneda's second part when he published his own sequel in 1615.

For modern Hispanists, the so-called False Quijote is something of a curiosity, a quaint literary item that many have heard about but few have actually read with any real intensity. In all, there have been fewer than twenty editions of Avellaneda's work published since the appearance of the original version, only six of them in the past fifty years. Of these, the most celebrated is Martín de Riquer's three-volume Clásicos Castellanos edition, a welcome addition at the time of its publication (1972), but a work whose critical apparatus is now considered somewhat passé. Thanks to Gómez Canseco, those of us with an interest in the Avellaneda text now have access to a singlevolume edition that includes a first-rate introductory study, a very useful bibliography, and much more.

In his lengthy introduction Gómez Canseco is quick to point out that Avellaneda was hardly the first to imitate or parody Don Quijote while Cervantes was still alive; Salas Barbadillo, Francisco de Ávila, and Guillén de Castro all published material based on Cervantes' creation in the years immediately following 1605 (10). Avellaneda's primary objective, according —263→ to Gómez Canseco, was to astonish his readers while indoctrinating them in matters of faith; provoking laughter was a secondary objective (15). Another strong motive was Avellaneda's fervent desire to settle some unspecified accounts by pillorying Cervantes and his work in a widely disseminated document. Cervantes, of course, had the final word in his own sequel, with the result that Cervantine critics over the centuries have undertaken a campaign to cast Avellaneda's opus as one unworthy to be mentioned in the same sentence with the original. Only in recent years have some critics, among them E. C. Riley and this reviewer, recognized the need to look at the 1614 work with greater objectivity.

A large portion of the introduction deals with the critics' centuries-old search for Avellaneda's true identity («Pesquisas en torno a Avellaneda»). Gómez Canseco concludes this section with a bold and interesting hypothesis of his own: that Avellaneda's Quijote was in fact a collaborative effort undertaken by several friends of Cervantes' nemesis, Lope de Vega, who not only gave his consent to the project but may indeed have taken a proactive role in the preparation of the manuscript (59). With regard to the pseudonymous author's peculiar ideological bent, Gómez Canseco concludes that Avellaneda was a religious as well as a social conservative, a man devoted to the rosary (there are thirty references to it in the work) and obsessed by the issue of moral decay that threatened to erode the very fabric of Spanish (i. e., Catholic) society.

On the question of efficient versus sufficient grace, Avellaneda was strongly influenced by the Dominicans who maintained -along with John Calvin, curiously enough- that the human will was ultimately not free to reject an offer of divine grace from God. This position was rejected by Molina and the Jesuits, who supported a much broader concept of human free will. In sum, this was a very divisive issue among seventeenth-century Catholic theologians, one that the Roman Church was never able to resolve. Avellaneda was also a staunch defender of the political status quo; he argued for a strong social order, along with a powerful political hierarchy to uphold it; for him obedience was a prime social virtue. Gómez Canseco maintains that Avellaneda's socio-political fervor impelled him to compose an expurgated version of Cervantes' radical novel; in the sequel all of Cervantes' subtle social criticism would be replaced by a right-wing agenda. In Avellaneda's view, a radical thinker like Don Quijote clearly belonged behind bars, and that is precisely where Avellaneda left him.

Another portion of Gómez Canseco's introduction discusses the internal structure of Avellaneda's story, as well as the various narrative voices that the author employs in telling it. Of even greater interest, however, is his analysis of Avellaneda's heavy-handed treatment of the two protagonists (i. e., turning them into caricatures and stereotypes, rather than the sublimely interesting individuals that Cervantes fashioned for his readers). Gómez Canseco also discusses some of the more notable secondary characters who —264→ appear in the 1614 tome (Bárbara, D. Álvaro Tarfe, mosen Valentín). He closes with an insightful investigation of the novel's two interpolated tales, «El rico desesperado» and «Los felices amantes». The first of these is an exaggerated version of an already violent story by Bandello; the second is simply a modernized adaptation of a medieval legend (Cantiga 94 of Alfonso el Sabio's thirteenth-century collection).

The ten-page bibliography is quite impressive, citing 17 editions of Avellaneda's book and referencing a total of 97 critical studies on the work. Also included is a very useful Cronología that cross-references the principal literary, historical, political, artistic, scientific, and cultural milestones of the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. The text of the novel itself (pp. 191-721) is followed first by a series of indices. These include a catalogue of literary sources (biblical, Greek, Latin, patristic, scholastic, etc.), an alphabetical list of proverbs cited by Avellaneda, and a useful lexicon of special words, colloquial expressions, and proper names (with page references). A supplementary Aparato crítico features a chapter-by-chapter index of variants from the several editions of Avellaneda's text.

With regard to more technical matters, the volume has relatively few typographical errors in the Spanish text; the citations from English-language sources, however, often contain annoying misspellings, as on page 15 where «from» is given as «form», followed by non-existent forms like «openning» and «Cervante's». In all fairness, these infelicities are a small price to pay for an excellent critical edition of Avellaneda's False Quijote, a work that is both a literary curiosity and a very pleasant read. Even more important, however, is the way in which Avellaneda's modest work serves as the perfect foil to demonstrate the sophisticated literary genius behind Cervantes' original.

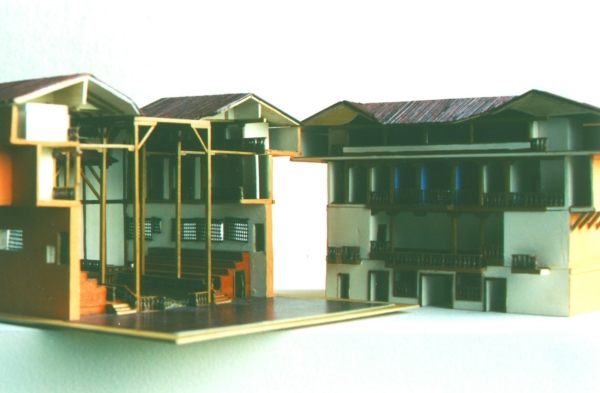

John Jay Allen's Model of the Corral del Príncipe