The General Estoria: Sources and Source Treatment

Daniel Eisenberg

The General Estoria of Alfonso el Sabio -the work he thought of as his greatest- has yet to receive the attention it deserves. To scholars interested in Spanish history, such as Menéndez Pidal, it does not have the appeal of the Primera crónica general, and as a historical source per se its value is slight. The most important reason for the work's neglect, however, is its considerable size, the main cause of its remaining unpublished until recently1. As yet, only two of the six parts2 have been printed.

It may be in order to reacquaint the reader briefly with the work. It is, as the title suggests, a «general» history, intended to include everything known of the world up to Alfonso's time. A modern history of Western civilization, with some additions, would parallel it. The idea was nothing new, but the extent was: in an age given to extremes in length, it is a voluminous work. It is not surprising that it was never finished; with the death of Alfonso in 1284 it was abandoned. We know of five parts (of which three have reached us intact) and a fragment of a sixth, which take the work up to the legendary parents of the Virgin Mary. The first of the two parts published contains world events up to the death of Moses, while the second continues to the death of David3.

Although less than half the surviving text is available in print, that portion in itself is large enough that several types of investigations may be based on it. The present study is intended as contribution towards a definitive study of the sources of the GE, which must await the complete publication of the work. Rather than classify sources by period or religion of the author, I have done so by the degree of utilization which Alfonso made of them. First I will speak of those sources which, because of their chronological structure, were used more or less continually. Then I will discuss secondary ones which contributed segments of the narration, but only occasionally, and finally mention the illustrative sources to which he refers in passing. Following this, I will add some comments on his editorial practices.

The GE differs from the PCG in an important respect: in the GE Alfonso usually names the sources he takes his information from4. This is not, however, an unmixed blessing, as direct and indirect sources appear indiscriminately. As often as not, the direct source from which a quotation is taken will be indicated (as on I, 172b, where he tells us that the comments of «Temosten, e Eratostem, e Artenidor e Esidoro» on Egypt are taken from Pliny). Other times it can be found mentioned not far away in the text (I, 31 b: «Beroso el Caldeo», «Iheronimo de Egipto», and «Maniseas de Damasco», all via Josephus). On many occasions, however, this is not the case, and the work in question is not so unusual as to render a direct consultation impossible. Such is the case with Cicero («Tullio»). It is often only luck which reveals the source: in this case, the Pantheon of Godfrey of Viterbo (compare I, 76a and 550b with Pantheon, p. 65)5. Furthermore, the same author may appear quoted indirectly via two different sources. This is the case with the Biblical commentators such as Augustine or Rabanus Maurus, found both in the Glossa Ordinaria and in Petrus Comestor. An author may be cited both directly and indirectly (for example, Josephus). Even third-hand quotations are not rare (v. I, 14a - Josephus quoted via Rabanus Maurus via the Glossa Ordinaria).

It is not surprising that Alfonso indulges in displays of erudition. He thus confuses the matter further by giving lists of sources, for example: «Segund los esponedores dela Biblia - Augustin, Iheronimo, Beda e otros» (I, 37 b); «Asia, segund dize Plinio, e Paulo Orosio, e el Libro delas Prouincias, e mahestre Galter enel Alexandre, tiene tamanno termino commo las otras dos» (I, 45a). Often these lists verge on the humorous, as: «Del Nilo como nasce, e delos logares o paresce e poro passa, fablaron muchos sabios como Aristotil, e Tholomeo, e Plinio, Eratesten, e Homero, e Themosten, e Artemidoro, e Esidoro, e Muciano, e Lucano e Paulo Orosio» (I, 112b). To «prove» that Alfonso did not consult all these would be difficult, but in the course of investigating direct sources, it has been revealed that the large majority of sources mentioned in such lists are indirect.

Alfonso also gives additional authority to his statements by implying that he has consulted other, unnamed sources: «diz Maestre Pedro, e otros con el» (I, 151 a) ; «Josepho e otros» (I, 151 b) ; «et cuentan Iheronimo et todos los otros» (I, 153b); «assi como dizen Ouidio e Estacio e otros» (I, 172b), etc. Similarly, it is impossible to prove that he did not consult the «otros», but they have not yet come to light. The frequency with which they are cited, coupled with Alfonso's consistency in naming his sources, suggests that this is only a rhetorical device6.

Alfonso's sources were, on the whole, Latin ones. Although he made some use of Arabic and of French ones, quantitatively they were minor. He shows no knowledge of Hebrew7, nor, more important, of Greek. This is an important clue in the clarification of sources, for it means that a Greek author cited must have been available in a pre-existing translation, presumably a widely disseminated one (Eusebius, Josephus, the New Testament), or be mentioned indirectly. Thus, although I have not discovered the source of the references to Theodotion («Teodocio, en el otro traslado que el fizo dela Biblia», I, 29a, 390b, 399b, 402a, 591a, 593b, 748a, etc.), or to the Septuagint, I am confident that one will appear8.

I have not thought it necessary to mention, except in passing, sources which are unquestionably indirect; any that are cited in the published text and are not mentioned may be assumed to be so9.

Although the actual sections of text it contributed are small, the work of Eusebius of Pamphilus (c. 260-c. 339) should be considered first. The Chronici canones, which reached Alfonso in the Latin translation of St. Jerome, is truly the «spine» of the GE, giving it a structure which is lacking in other compilations such as the Speculum historiale10. It is a year-by-year chronology, beginning at the birth of Abraham. Along with the patriarchs and other Biblical leaders, it lists in parallel columns the years of the reigns of rulers of principal kingdoms. In the margins are indicated the principal contemporary events, including «mythological» ones: «Harmonia rapta a Cadmo», and the like. The importance of this work becomes particularly obvious in Part II of the GE (apparently little of note happened in the period up to the death of Moses, part of the reason Eusebius went unappreciated before11). If Alfonso decides to go off on what seems a tangent and talk about Crete in the middle of Joshua, (II, 1, 31b ff.), it is because Eusebius (p. 46b) puts at that time a note: «In Creta regnauit Lapis». Similarly, he talks about Europa and Jupiter (II, 1, 52b ff.) because Eusebius notes (p. 47b) «Europae, filiae Foenicis, mixtus est Iuppiter». He mentions «Pandion rey de Atenas e de sus fijas» (II, 1, 137a), because Eusebius notes (p. 47b): «Pandion filius Erichtonii, cuius filiae Progne et Filomela», but promises a full account later, «ca en aquel tiempo lo cuentan Eusebio, e Jheronimo, e los otros sabios en sus Estorias». The examples are numerous. It would seem that Eusebius was consulted first, Alfonso proceeding with Biblical material when, and only when, Eusebius showed him that there was nothing secular to narrate.

Eusebius' notations also served Alfonso as his text, when he could find nothing more extensive. He expanded them as best he could: Eusebius' note «Ogygus in Attica Eleusina condidit, quae antiquitus uocabatur Acte, et alias plurimas ciuitates» (p. 30 b), becomes: «... regnaua en Grecia un rey que auie nombre Ogiges Matica12, e este rey Ogiges poblo, en aquella tierra de Grecia o el regnaua, una cibdad por cabeça de su regno, e el logar daquella çibdad auie nombre antigua mientre Acta; e el rey Ogiges, quando la poblo et la fizo grand e noble, tolliol aquel nombre e mandola llamar Eleusina o Eleusis; e fizo otrossi por su regno otras muchas cibdades e pueblas». (I, 186a). Another example, in a different section, is at II, 2, 230a, where he takes from Eusebius (p. 65a) information on the «siçionios». At other times, Alfonso has done nothing but copy the names of kings and the years of their reigns from the table, one after another. One example should suffice: «E andados LXIIIJ annos dela seruidumbre, e XXIX del Pharaon Amenoffes, e IIIJ del nascimiento de Moysen murio Spero, rey de Assiria, e regno empos el Manulo, XIIIIº rey dalli, XXX annos. Andados LXVIIJ annos de la seruidumbre, e XXX del Pharaon Amenoffes, e VJ del nascimiento de Moysen, murio Creago, rey de Argos, e regno empos el Phorbas, VJº, rey daquel regno, XXXV annos. Andados LXX annos dela catiuidad, e IIIJ del regnado de Manulo, rey de Assiria, e VIJ de Moysen murio el rey Pharaon Amenoffes de Egipto, e regno empos el el rey Horo, VIIJº Pharaon, XXXVIIJ annos» (I, 304a, corresponding to pp. 39-40 of Eusebius).

Eusebius also furnished Alfonso with many indirect quotations: «Castor el Sabio» (II, 2, 229b), «Filocoro» (II, 2, 37b, 262a), «Eraches», «Eratostenes el sabio», «Aristarco», and «Apollodoro» (II, 2, 262a); etc.

The most important single source of the GE is the Bible, obviously the Vulgate13. Besides its sacred importance, the Bible was the most accessible source of ancient history in the Middle Ages. Alfonso does not treat the Bible with an unquestioning reverence. There are many instances in which it can be shown that his attitude towards the Bible was much the same as towards any other of his sources. Although he includes all the Biblical books, he does not do so word for word. When it is to his purpose , he unhesitatingly deletes verses, or abbreviates a whole passage. Note, among many others, I, 335a, 347b, 449a, or 519b, where he skips from verse to verse, or I, 538a, where he cuts short the discussion of «unas cosas uergonçosas de dezir que suelen a algunos uenir de los judios uarones», obviously motivated by modesty14. At I, 184a, he omits almost ten verses of Genesis 31, as unnecesary.

Alfonso's editorial criteria led him to compare the Bible with his other two major sources, Josephus and Petrus Comestor. Over and over occur formulas such as «cuenta la Biblia e maestro Pedro», «ca los unos dizen, como Moysen e Maestro Pedro», which would be superfluous, if the Bible were accepted without question as the literal truth. On other occasions, he takes the Biblical material directly from his other sources, instead of from the sacred text. For example, see the indirect quote via Petrus Comestor on I, 137b (Petrus Col. 110315, corresponding to Gen. 20:16).

A considerable error led Solalinde to state that Alfonso based his Biblical exegesis on the works of «Origenes, San Augustín, Beda [y] Rábano Mauro, sin contar varias glosas anónimas» (I, XII-XIII). In fact, he did no such thing; the only gloss in question is that which is known as the Ordinary, which includes all the above material. The Glossa Ordinaria, falsely attributed to Walafridus Strabo (c. 808-849)16, was a collective and accumulative work, consisting of both interlinear and marginal notes made in Bibles and passed on from generation to generation of copyists. They mainly took the form of quotations from the commentaries of the Fathers, indicating the source they were from. Alfonso's Bible contained an earlier form of the Glossa than that printed by Migne, since he apparently did not use many of the commentaries found in Migne's edition -those of Isidore, Chrysostomus, Procopius, Hilarius, and Alcuinus among others. As the evolution of the Glossa Ordinaria remains unstudied except in a very general way17, an attempt to specify Alfonso's version is impossible.

From the Glossa Alfonso takes many details: the Hebrew names of the books of the Bible and their meanings, the prologues of Jerome to Numbers and I Kings, and incidental material such as the fourth penitential psalm (I, 592b). He turns to it constantly for elucidation; not knowing the proper way to refer to it, he calls it «la Glosa», or uses the formulas «fablaron los sanctos Padres», «segund los esponedores dela Biblia», «fallamos por escriptos de sabios», and so on. The work in question is always the same.

Most important for the clarification of sources is that the Glossa furnished Alfonso with a large number of indirect quotations. Some of the material is found in the Glossa (as published by Migne) unnamed (for example, «Esiodo» or «Eliodoro», I, 553b, 573b), or otherwise garbled, but by and large the identification of commentaries cited by Alfonso is both easy and definite. In the case of Rabanus Maurus, for example, at all but five places where his name appears (I, 14a, 110a, 153a, 307a, 342a, 6 18a; II, 2, 279a, 313a, 321a, 327a, 328b, 330b, 334a, 335ab)18 the same information appears under his name in the Glossa. One of the remaining ones (I, 145ab) is via Petrus Comestor, and one (II, 2, 319b) is apparently a mistake, as the information he says is from Rabanus Maurus is present in the Bible. Thus only three (I, 430a, 622a; II, 2, 325a) remain dubious. Quotations from Gregory are similarly all from the Glossa (I, 7b, 34b, 348x, 412b ff. ; II, 2, 298b, 30 4b), though in Migne's edition most are there under another name, or anonymously.

In the case of Augustine, the citations are too numerous to be listed. A selection will have to suffice: I, 5a, 32a, 70a, 344b, 390b, 419b, 427b, 553b, 630a, and II, 2, 299a, 335a, all come from the Glossa. Others (I, 337a, 523b) come from Petrus Comestor. Still others, oddly enough, come during commentaries on Ovid (II, 1, 211a, 216b), suggesting that he was cited by the «frayle» whose comments formed part of the Ovidian gloss before Alfonso19. Others, it must be admitted, are not in the Glossa as published (I, 142b, 363b, 413a), but neither are they in Augustine's Quaestiones or Locutiones, his only systematic commentary.

The systematic commentary of Origen was certainly not used. The name of this controversial commentator occurs frequently, but usually in lists (I, 441a, 461a, 484a, 493a, 510a, 572b, 591a, etc.) Most of the remainder come via the Glossa (I, 373b, 39 9-401, 409b, 410a, 552-553, 630a, 677b) ; an occasional one via Petrus Comestor (I, 671a, II, 1, 6a). The only dubious place is at I, 485-1186, on the tabernacle described in Exodus. Similarly, a passage on the tabernacle (I, 446 ff.) is the only place where the direct influence of Bede cannot be definitely excluded; he wrote a treatise on the subject. Apart from this passage, and one quote via the Glossa (I, 4b), his name only appears in lists (I, 37b, 85b, 341b, 510a, 591a, etc.)

Jerome is quoted for exegesis as well as for his translation, in which context his name more frequently appears20. The material again comes from the Glossa (I, 26a, 32a, 48b, 141a, 143a, 153ab, 180b, 378a, etc.) Other times, explanations attributed to him are found in the published Glossa under someone else's name (I, 412b), or anonymously (I, 20a). Others come via the indispensable Petrus Comestor (I, 27b, 121b, 135a), and a handful are unidentifiable (I, 109b, 622a)21.

Flavius Josephus (37-c. 100) included in his Antiquities of the Jews material -often of a colorful nature- not found in the Bible, and Alfonso drew on him frequently for material to supplement the Holy Scriptures. Josephus as used by Alfonso is the subject of an article of María Rosa Lida22, to which the main thing to add is that the Latin translation which Alfonso used is now available in a critical edition23. Alfonso's text belonged to the «Y» family of manuscripts, as do the three MSS which according to editor Blatt exist in Spain24.

Only slightly less important than Josephus is the Historia Scholastica of Petrus Comestor (c. 1100-c. 1180), referred to by Alfonso as «maestre Pedro»25. This basic work of the Middle Ages was so popular that it came to be used in the universities a longside the Sententiae of Petrus Lombardus, hence its title26. It embodies, in miniature, many of the features of Alfonso's work, and to some extent served him as a model. The two works have in common a Biblical framework, the inclusion of other elements, the reference to various authorities and an occasional attempt to reconcile their differences. Alfonso, however, includes many times the extra-Biblical material that Petrus does, and expands on it, while Petrus abbreviates. The references to Petrus are almost constant throughout the Biblical material, particularly in Part I. He generally appears simultaneously with the Bible text in question, as opposed to Josephus, who can stand alone in an independent chapter. Petrus Comestor is also an important source of indirect quotations; besides the ones already mentioned, one can add Amphilus (I, 42a), Aquila and Symmachus (I, 169a), Strabo (I, 386b), Methodius (I, 83a, 141a), Josephus (I, 398ab, 424b, 425b), Augustine (I, 398ab, 424b), and others.

To exhaust the list of basic sources of the GE, we need only add the Pantheon of Godfrey of Viterbo (1125-c. 1200), or «maestre Godofre», as Alfonso calls him. This work also draws heavily on the Bible, particularly in its early sections, and has a theological prologue. Alfonso rejects it for Biblical material, except for elaboration on important (i. e., royal) characters which the Bible passes over quickly, as, for example, Abimelech, king of «Gerara» (I, 136-137). It is more extensively used with regard to contemporary pagan events. Thus, information on the kings of Babylonia (I, 73b ff.), Jupiter, king of Athens (I, 198b), Greece (I, 258a) and similar items are from him. He is used most during, roughly, the first half of Part I.

The most recent complete edition of the Pantheon remains that included by Pistorius in Volume 2 of his Germanicorum Scriptorum (3rd ed., as Regensburg, 1726). Only sections are printed by Waitz in Vol. 22 of the Monumenta Germaniae Historica Scriptorum series (Hanover, 1872). Unfortunately, the edition of Pistorius follows those MSS which Waitz labels «C» and «D», whereas Alfonso used a later revision represented by the «E» MSS. The chapter numbers Alfonso gives («Et dize sobresto mahestre Godofre enla sexta parte del Panteon») thus do not agree with the divisions in Pistorius' text. The parallel text summary printed by Waitz (pp. 107- 112) resolves the problem for the earlier sections of the work.

Of the secondary sources, which contributed isolated sections to form an appreciable part of the GE, several have received attention already. María Rosa Lida has commented considerably on Alfonso's treatment of Ovid27, and J. R. Ashton has explored his relation to the Heroides textual tradition28. Suffice it to say that 30% of the Metamorphoses, and 8 of the 21 epistles of the Heroides are included in Parts I and II of the GE alone. Kiddle has studied the story of Thebes, which appears as an un interrupted whole in Part II (II, 1, 325-387), and concluded it to be based on the French prose redaction of the Roman de Thèbes, which is unavailable in print29.

Neither have Alfonso's two main Arabic sources been edited. The better known of them, Abû 'Ubayd al-Bakrî († 1094) was originally identified by Menéndez Pidal30. Yet his most famous work, Kitab al-masâlik wal-mamâlik, which is cited by name by Alfonso (I, 208b), is a geographical guidebook and is with difficulty reconciled with Alfonso's precise reference to the «XXI capitulo del su Libro sobrel nascimiento de Abraham» (I, 86a). «Abul Vbeyt», as Alfonso calls him, besides contributing sections regarding Abraham, may have been a source for Alfonso's retelling of the story of Joseph (I, 208-221). The details of the formation of his version of this story are unclear -Christian authors also played a part- but another Arabic source which contributed is that referred to as the «Estoria de Egipto», which Solalinde (I, XIII, n. 1) identifies as the work of Ibrahim Benuasif Xah el Misri (7th cent.) He is cited with some frequency to complete the brief references of Eusebius to the Pharaohs, and to correct them. Arnald Steiger has attempted to locate the sections Alfonso refers to, but without success31. Solalinde stated that these two authors were his only direct Arabic sources32.

For the main body of the narration of the story of Troy, Alfonso used the version commonly attributed to Dares Phrygius33. The choice of his work over the Ilias latina or another medieval version was not difficult; he was taken as an eyewitness to the events he retells34. The reasons for the rejection of Dictis Cretensis, who in many manuscripts appeared together with Dares, are not so clear. Alfonso may have been attracted to Dares because of his simplicity of language, his brevity, or perhaps because he considered a Trojan to be more reliable. Almost the whole work was utilized, though somewhat rearranged, with occasional interruptions to insert identified (Heroides V) and unidentified material35.

The text from which Alfonso worked belonged to the «G» family of Meister, which represents the alternate recension postulated by Courtney. Thus, G and Alfonso (II, 2, 124ab) read «forty» for «twelve», at II, 2, 124al1-12 read «sixty» for «forty», etc. Alfonso's text had, however, many more variants than the version Meister reproduced, some of them showing that either Alfonso, or some one in the MS chain he belongs to, had difficulty in reading the text: II, 2, 123b42, «Telion» for «Tesion» («Teƒion»); II, 2, 123b43, «Nestor rey de Pilo», from a run-on reading of «Nestor ex Pilo».

The Natural History of Pliny the Elder (23-79) is also among the most important of secondary sources36. A substantial part of Book VIII, on the mammalian inhabitants of the Nile, is included in the published text (I, 222-224, 293-295, 555-570), along with notes on geography, from Book V (I, 112-113, 172, 275-279, 310-311), and on dolphins from Book IX (II, 1, 181-187), as well as other material. He is mainly used in short passages, and Alfonso must have been grateful for the foresight with which Pliny prefixed to his book what is essentially an index (Book I), making the location of selected topics fairly simple.

The text of Pliny is quite corrupt, and the lectio vulgata variants which the Teubner edition gives support many of Alfonso's misreadings: «Ffabio» for «fabulis» (I, 559b2), «Ita Copas» for «Item Apollas» (I, 559bl3) (these noted by Solalinde, I , XVII, n. 2), «color» for «olor» (I, 558b46), «Libia» for «Iuba» (I, 55020), «Siria» for «Syrtes» (I, 569bl7), etc. Many are not represented in the notes, however: «don Meneto» for «Demaenatum» (I, 559b15), «Hismaco» for «Hyrcanus» (I, 56015), «Vlix bona» for «Olisiponem» (I, 564a53), and many, many others. There are also places where the sense is much confused: v. I, 560a36-41, 562b3l-34.

The names of Pompeyus Trogus, a Greek historian, and his abbreviator and translator Justinus (3rd century?) only appear twice in the work (I, 210b, 534a), in the guise of Arabic or Egyptian historians, thus confusing Solalinde (I, XIV), who did not realize that these references came via Paulus Orosius, I, 8 and 10 (see below). It would be strange, though, if this work, much used in the PCG, played no part in the GE. Although it is not cited by name -one of the few cases where a source is not- the entire story of the foundation of Carthage (II, 1, 431 ff.) comes from Book XVIII of Justinus37, as does the same episode in the PCG. The «Estoria de Assiria» which supplies information on the kingdom of Athens (II, 2, 305-307) is likewise Justinus38.

A Latin «Estoria de las Bretannas» appears, following the Troy story, to narrate the accomplishments of Brutus, a descendent of Aeneas who, after many adventures, arrives in England (II, 2, 263-279, 305a). This turns out to be almost the entirety of Book I (Chapters 3-16 and a note from 17) of the Historia Regum Bretanniae of Geoffrey of Monmouth († 1155). Alfonso cites twelve verses of his text (II, 2, 272) on the prophecy of Diana. As Entwistle has noted, all of Geoffrey's work through Book III, Chapter 8 (excluding the two opening chapters) is included in the GE, spread through Parts II, III and IV39.

A considerable passage (Book X, 172-331) from the Pharsalia of Lucan (39-65) appears in the work (I, 115-120) ; it concerns the response of Acoreus to Caesar's questions concerning the Nile. The Pharsalia will appear translated in its entirety in Part V40.

In concluding our discussion of the secondary sources, it may be of use to mention that the chapters of Alexander from Part IV which Solalinde has included in his anthology come from the anonymous Historia de Praeliis41. There are, in Parts I and II, several references to the work of «maestre Galter», the «Estoria de Alexandre el Grand e de Dario»: I, 45a, 48a, 51b, 399b; II, 1, 90b; II, 2, 164b). This is the Alexandreis of Gautier de Châtillon (fl. 1175), the work which served as a basis for the Libro de Alexandre. This latter work, Solalinde has noted, is used for the judgement of Paris at II, 2, 107-10842.

The final group of sources are those which I have termed illustrative. They were not used as a basis for the text, but to shed additional light on the material already at hand, to supply an odd fact here and there, or to give statements greater authority (the equivalent of the modern foot note). All of them are mentioned in passing, some only once; some may be based on memory, or be indirect. I treat of them in a rough order of decreasing importance.

We can begin with «el sabio don Lucas», familiar from the PCG43. The Chronicon mundi of Lucas Tudense († 1249) was too brief to serve as a basic source for Alfonso44. Lucas appears cited with some frequency for elucidation on, by and large, Biblical material. As he is often mentioned when discussing the ages of the world, it can be assumed that Alfonso took this information from him, rather from Ovid or a work based on him.

The Historium adversus paganos libri septem of Paulus Orosius (fl. 430) offered in the first book a condensed account of events from the flood to the founding of Rome, along with a short sketch of world geography45. This last, along with Isidore of Seville (see note 47) furnished Alfonso with his geographical information. He also supplied Alfonso with indirect quotations, on Justinus (as noted above) and Tacitus («Cornel», I, 360).

For etymological information, Alfonso used a popular work of Huguccio of Pisa († 1210), the Magnae Derivationes46. Another frequent source are the «esponamientos de Ramiro», which Solalinde has identified with the Interpretationes Nominum Hebraicorum, attributed to Remigius Autissiodorensis (c. 841-908)47. Papias is only mentioned twice.

The Thebaid of Statius (40-c. 96) was promised by Alfonso to his readers at II, 1, 84a, and then neglected in favor of the Roman de Thèbes, as Kiddle has noted48. He cites the Achilleid, however (II, 1, 276a; II, 2, 48b, 49ab, 126b, 162a), for details on the Troy story, although his quotations are hard to locate. He also quotes its «esponedor» for the information that an artistically told story begins in the middle (II, 2, 48b), yet this nugget does not appear in the commentary ascribed to Lactantius Placidus49. It has been established that he used Servius' commentary on Virgil50.

«Un libro que fue fecho en India, et a nombre Calida e Dina» (I, 197b). The episode of the trip of Berzoe or «Barzeuay» to India is told; it does not correspond to the familiar Spanish version51 in an important detail: that the initiative for Berzoe's trip comes from the King of Persia. This is not because it was based on memory52 - Alfonso says «fallamos... esto en un libro» -nor because of literary elaboration by Alfonsine collaborators53, but because the Arabic text was different54. If Alfonso himself were not present, it need not be taken for granted that his collaborators would know of a translation made over twenty years earlier. That two Arabic MSS should come to hand at different times is more than possible.

Another oriental source is the «libro de Marçal, e con el Mesealla otrosi que fue descobridor de las poridades de Hermes» (II, 2, 337-342). Masâllâh was a Jewish astrologer (fl. 800) writing in Arabic, some of whose works were translated into Latin; «Marçal» remains unidentified.

Alfonso comments on the «latin muy fermoso e muy apuesta mientre ordenado» of «una Summa de la Rectorica» (II, 1, 57a), and includes a quotation55. It is suggestive of Martianus Capella's De nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii, particularly since it comes with regard to Mercury's knowledge of the trivium and quadrivium. Yet the passage can not be located there56.

«Maestro Ebrardo enel Libro del Grecismo, e otrossi enel Libro de las Penitencias» ... «o fabla de cinco yentes que diz que a en Grescia e aun mas, departidas por sos nombres e sus tierras» (I, 206x, 505a; II, 1, 278ab, 297b). This refers to the popular Graecismus of Ebrardus Bithuniensis (early 13th century), yet his conception of its contents is curious, as the work is a grammatical, not a geographical, treatise57. The «Penitencias» book remains unidentified.

The Chronographia of Sigebert of Gembloux († 1112), often used in the PCG, comes in for occasional mention (I, 208b; II, 2, lb, 37b, 46b). «El emperador Justiniano... en un libro que fizo de derecho e llaman le Instituta» (I, 580b) requires no explanation. «Anastasio en el psalmo Quicumque uult» (I, 413a) refers to the Athanasian creed, a profession of faith in the trinity. «Pedro Riga enel libro que fizo delas estorias dela Biblia a que puso nombre Aurora, en que cuenta por uiessos toda la Biblia» (I, 364a) refers to Petrus de Riga (c. 1140-1209), a well-known church author58. Alfonso quotes five verses, on the ten plagues of Egypt.

«Maestre Pedro chançeler de Paris... en las Sentencias» (I, 474a), refers not to Petrus Lombardus, but to his disciple, Petrus Pictaviensis (c. 1130-1205)59. «Maestre Pedro en el Libro de las generaciones del Uieio Testamento» (I, 36a, 83a, 99b, 100a, 263a, 266a, 665b) must refer to his Compendium Historiae in Genealogia Christi. The verse work referred to as «Celum factum» and the treatise on the sacraments (I, 487a) are to found in PL Vol. 171 attributed to Hildebrand, according to Shoemaker60.

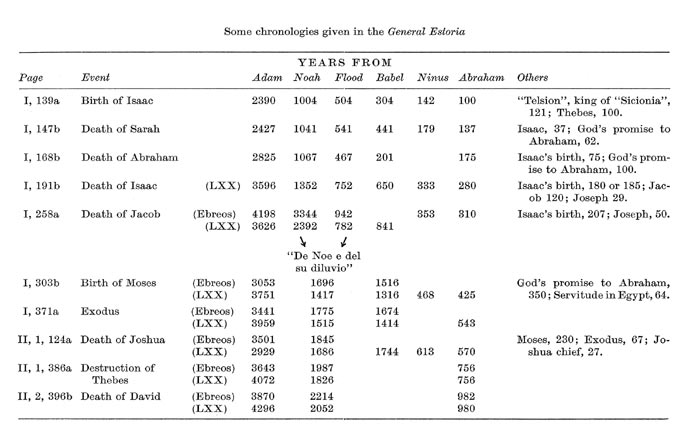

There are a few sections of the work where no source is mentioned and for which none can be found61. In particular, the sections on primitive man (I, 61 ff.), on the Hebrew festivals (I, 624-626), on Aristotelian causes (I, 465) and on Hypermenestra (I, 762 f.) have not been adequately explained. Nor have the chronologies which Alfonso inserts in his work been traced to their source. These are scattered throughout the work, giving the time between important landmarks (the creation, the flood, «el departimiento delas lenguas») and the important event which occasioned the chronology -frequently a death62. He also gives the reigning kings at the time. The much less extensive chronologies in the PCG Menéndez Pidal indicates repeatedly as being the work of the editor, which the small type of chronologies which occasionally head chapters in the GE may be (as at I, 31). However, this does not seem likely in the case of the extensive lists of figures to which I have referred above. At one place, he says he takes them from the Compendium Historiae of Petrus Pictaviensis (I, 263a), yet this seems unlikely, at least in view of the fragment reproduced by Moore63. He also says that they are taken from Godfrey of Viterbo (I, 262b), yet the considerable difference between the figures each gives makes it unlikely that the Pantheon could have been more than a model. Here, for comparison, are the chronologies of both at the death of Moses:

| (I, 767,b) | ||

| (p. 96b) | ||

The enormous inconsistencies in the figures (see table) suggests textual problems in a definite source work, rather than independent construction of them by Alfonso. Neither can a possible base for his figures be found. Eusebius is his usual source for chronological material, yet I am unable, by any combination of the figures given by him or in the the two prologues published by Schoene, to arrive at any figures which approximate Alfonso's, even allowing for a moderate amount of textual confusion64. I am also unable to explain the sudden appearance of the different computations of the Hebrew and the Septuagint, or the simplification in Noah's position.

A discussion of Alfonso's sources raises problems as well as solves them. How is it that Alfonso knew Isidore's Etymologies, the medieval work by which Spain was best known in Europe, only in a fragmentary version, with the wrong title and no author? How is there not a mention of Vincent of Beauvais' Speculum historiale, which we know was used when writing the PCG65

When the text of the GE has been completely published, a thorough comparison with the sources of the PCG will doubtless raise other questions of this type.

More important than this, however, is to evaluate the editorial standards, to determine how Alfonso chose and combined his sources to produce a whole. There are certain tendencies, if not hard and fast rules, which can be pointed out. María Rosa Lida has noted that Alfonso states an intent of including everything (II, 1, 130b)66. Thus, he often criticizes his sources for not being more complete. For example: «Mas delos nonbres delos reyes deste regnado de Egipto non fallamos y delos primeros ciento e IX annos, otros nombres de reyes si non que regno el linage de los thebeos» (I, 99b); «E dizen todos que [Ahilon] duro en el sennorio del alcaldia diez anos; mas que ninguna cosa poca nin mucha que de escriuir fuese, nin lo escriuieron los santos padres en la Bribia, nin los esponedores, que aquel Ahilon fiziese en estos diez annos» (II, 2, 47b). These notes often seem like attempts of Alfonso to justify himself67.

He is quick to note differences in names given by different sources: I, 413b, on the Pharoahs; I, 677b-678a on Biblical figures, as at I, 361b; I, 153a, on Abraham's wives, etc. Also, he notes differences in chronology, such as at I, 152. In this regard he must sometimes make an evaluation, such as taking Eusebius' figures over those of Godfrey of Viterbo (I, 613b). He sharply criticizes the Bible on one occasion for not telling its story year by year68.

Beyond this, however, his editorial practices are at best enigmatic. Although at some point he usually gives the credentials of authors he quotes, these often seem more like a justification of their use than a true explanation of why they were chosen69. Often they are just a tag: Eusebius was «un sabio delos caldeos» (I, 199b), etc. María Rosa Lida is correct in rejecting esthetic considerations for the choice of Ovid or Lucan, yet even her own examples do not show consistent use by Alfonso of the longest version. The Pharsalia's comments on the Nile are not markedly longer than those of Pliny, and in any event, why use half of Pliny, and then suddenly abandon him in the middle? Likewise, there is no reason to say, as she does, that Alfonso used Pliny's descriptions of the habits of dolphins because it was the longest; surely the descriptions of dolphins which Alfonso had at his disposal were not numerous70. If he wished to include everything, how is it that the creation and the fall, the parts of the Old Testament most commented on, are told so briefly? Surely the opening received the King's direct attention, yet the creation is told in one summary chapter.

Questions of availability and familiarity certainly went into the selection of sources. Research on a particular question was, in the Middle Ages, not only difficult, but often unlikely to reveal anything new. If Ovid were available, and had the in formation needed, why not use him? He was considered as reliable as anybody. If Alfonso was familiar with Godfrey of Viterbo and his work71, he would be used as well.

Even in Part I, there seems to be no careful editing of material. Association is the only reason to speak of King Ninus (I, 76b; inspired by Petrus Comestor), then the «regno de orient», then Paulus Orosius' description of the four kingdoms of the world, and then, to balance his earlier description, the «regno de occident». Likewise, the passage on the Nile was suggested by the presence of Joseph in Egypt. Switching from the comments of Pliny on the Nile to those of Lucan is strained enough, but when the presence of Julius Caesar in this author produces a description of the Julian calendar, Alfonso's work seems more a collection of miscellanea than a history. Sources weave in and out without any apparent rhyme or reason: why is Godfrey of Viterbo so utilized in Book V, or Josephus all but absent from Book IX? The structure is also inconsistent: some books of Part I, such as XI, have elaborate prologues, describing in some detail the contents: most (XVIII-XX) have a brief one, but others (V and VI) have none at all. At times (notably in Leviticus) the beginning of each Biblical chapter will correspond with an Alphonsine chapter division, but at other times it is not noted in any way.

Ignoring the changes which printing has brought in the concept of editing, we could give Alfonso the benefit of the doubt and state that the work is unfinished, and therefore unrevised. But even this is avoiding the issue. The work is uneven; the beginning differs notably from the end of Part II. Even in Part I, the decreasing attention given to the successive books of the Bible is only partially justified by their contents; this decline is also notable if one looks at the decreasing length of each of Alfonso's own 29 books. In Part II, the decline in quality is yet more serious. The division into books is lost, the only divisions being those furnished by the books of the Bible (Ruth being treated as part of Judges). The chapters are no longer numbered; the notes when changing topic («Aqui dexamos las razones de... y tornamos a la estoria de...») are much less frequent. The number and variety of sources both decline. By the time we arrive at the book of II Kings, near the end of Part II, even Petrus Comestor and Josephus are almost absent, and the work becomes little more than a translation72.

A second and probably more important manifestation of the decline in quality in Part II is that the collation of sources which can be seen Part I (for example, the «estoria de Egipto» consulted along with Eusebius and the Bible for the story of Joseph) is absent. In contrast, we see stories treated as complete units, with little or no interruption: such is the case with the stories of Thebes, of Troy, of Hercules, and with shorter passages such as the one on Brutus. Long passages of Ovid are translated without regard for content73. Such a treatment means, of course, that a synchronistic structure must be abandoned, with apologies such as «Mas por que auemos dicho esta yda de Ercules a Troya e todo su fecho en la su estoria de Ercules que viene en esta General estoria ante desto, non dezimos ende agora aqui mas» (II, 2, 112a). Details of a story which are not included in the principal source (such as the Trojan horse, not mentioned by Dares) are simply tacked on afterwards, without much attention to the resulting incongruity. The work loses considerably in originality and importance by abandoning synchronicity, as it becomes only a collection of translations, arranged in a rough chronological order74.