The editing of Spanish Golden-Age Plays from early printed versions

Don William Cruickshank

The transmission of a text is not necessarily a process of continuous corruption and the introduction of errors. Corrections can be introduced by editors, copyists or compositors at almost any stage. These corrections may be made up (and so lacking in authority), or they may derive from another, more correct version. Corrections added to a manuscript or to a printed book after its production can usually be detected without difficulty; but if the corrected copy is used to produce a new manuscript or a new printed edition, the process of correction will be concealed, the identity of the corrector obscured, and the reliability of his corrections made uncertain.

An editor needs to discover as much as possible about the hidden areas of the transmission process. Unless he does, he will never know how close he has got to his ultimate aim, which is «to produce the text as finally approved by the author». One says «how close» advisedly, for the ultimate aim will often be unattainable. There will frequently be an unbridgeable gap between the manifestly defective surviving version and the version which the author must have produced1. In other cases, the editor's path to the «finally-approved» text may branch in several directions: to one or more manuscripts partly or wholly in the author's hand, and/or to one or more printed editions corrected (or possibly corrected) by the author2.

In the case of printed sources, the editor's task may be divided into seven different (though often closely related) parts. He will have to:

- Trace surviving editions and investigate relationships between them.

- Identify as far as possible those versions of his text which must have existed but which are lost.

- Identify the version to be used as the basis for his edition (the «copy-text»).

- Identify other versions which might be used to correct flaws in the copy-text.

- Decide what kind of edition to produce, given the nature of the copy-text and of other useful texts.

- Decide how much, and what kind of critical apparatus to include.

- Do the actual editing, with the many minor decisions which that involves.

Some of these parts are far more complex than others. The fifth and sixth ones are as likely, nowadays, to be influenced by financial as by scholarly considerations. Even the first one may be affected by the availability of funds. However, the suggestions which follow are intended to be governed only by scholarly principles. Editors must make up their own minds about cutting their coats to fit their cloth.

If financial considerations affect the production of modern editions of Golden-Age plays, they affected the production of the original ones even more. Both the theatre and the book trade were businesses, run by professionals out to make money. The dramatists were still amateurs by modern standards, but they soon discovered that it was better to write with performance than publication in mind: a stage manager would pay from 500 to 1000 reales (or more) for a play, while a publisher might baulk at 1003. As a result, plays were rarely published until their performing potential was exhausted -a process which might take years. During such a long period, many things might happen to the text of a play. The companies of actors who «owned» plays were under no obligation to perform them as the author had written them. They might make modifications: excisions, additions or revisions, depending to some extent on the abilities of the actors involved. The author himself might be involved in modifications, either because he kept in touch with the actors who had bought his play, or because he took the trouble to keep or acquire a copy of it to publish himself4.

There was money to be made in publishing plays, but not much. Profit margins were small, so that unless they were subsidised, printers and publishers had little incentive to try to restore a battered text to some semblance of correctness, or even to do what their technology permitted to preserve a correct one from error.

«To do what their technology permitted» is an important phrase: unless he has a grasp of the limits and potential of Golden-Age printing technology, the editor is not equipped to tackle his job. We must examine that technology before going any further.

Books of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were not produced as a series of single leaves, but as a series of large sheets of paper, each of them folded to make two, four, eight or more leaves, this is still the commonest way of making books, but many features have changed. Before 1550, Spanish plays were most commonly printed in folio format. After that date quarto prevailed, and eventually became almost universal. The terms «folio», «quarto», etc., refer to the number of leaves produced by folding the original sheet of paper once (folio, two leaves), twice (quarto, four leaves), three times (octavo, eight leaves) or four times (sextodecimo or sixteenmo, sixteen leaves). Their abbreviations are 2°, 4°, 8°, 16°. When a modern compositor sets a book, he begins at the beginning and goes on until he reaches the end. This did not become usual until the nineteenth century, because printing houses did not have enough type for a complete book, unless it was very short. Spanish printing-houses were particularly short of type in the seventeenth century: many had enough type of a given size for only eight quarto pages, or even less. As a result, production of a book did not involve the setting of the text, followed by the printing of the text, but the setting of a small portion of the text, which was then printed so that the type could be distributed to set the next portion of the text, and so on.

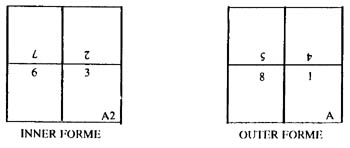

If the printer had enough type to set eight quarto pages, he could set them in their proper order: 1 (folio 1r), 2 (1v), 3 (2r), 4 (2v), 5 (3r), 6 (3v), 7 (4r). At this point, after only seven pages, he had enough to print one side of his first sheet of paper. In a simple quarto book, the inside of the first sheet, when folded, contains pages, 2, 3, 6, 7. It is known as the inner forme, and since its setting was usually completed before that of the outer forme, it was generally printed first. This straightforward, seriatim method of setting the text is called «setting by pages». Once printed, the two sides of the first sheet of the book would look like this:

As a guide principally for the binder, the compositor would put a «signature» at the bottom right of the first odd-numbered page (the first recto) of each forme, in the order A, A2, A3, A4, etc. Thus in a simple quarto book the first leaf will be signed A, the second A2; sometimes the third leaf (the second recto of the outer forme) is signed A3; exceptionally rarely the fourth leaf (se second recto of the inner forme) is also signed, A4. The fifth leaf, as part of a new sheet, will be B, the sixth B2, and so on through the twenty-three letter alphabet (excluding J, U, W). If there are more than twenty-three sheets, the twenty-fourth will be signed Aa, the next Aa2, the forty-seventh Aaa, the next Aaa2, etc5.

A printer who lacked the type to set seven or eight quarto pages seriatim would «cast off» parts of his text to set a forme. Casting off a verse play was easy, and merely involved counting lines and allowing for stage directions. Casting off prose required more care and experience. A compositor who wanted to set the first sheet of a play in quarto format by this method would cast off page 1, set pages 2 and 3, cast off 4 and 5, and set 6 and 7; this would complete the inner forme, at the cost of casting off three pages. It was possible to set page 1 first, cast off 2 and 3, set 4 and 5, cast off 6 and 7, and finally set 8, which would complete the outer forme, but only at the cost of four cast-off pages. Consequently, the printers' normal practice when using the casting-off method was to set the inner forme first, and so it would usually be printed first, just as it was in the «setting by pages» method. The correct name of the casting-off method is «setting by formes». It was slower than setting by pages because of the time spent casting off, and Christophe Plantin, an efficient printer with plenty of type, abandoned it in the 1560s. In Spain the method persisted throughout most of the seventeenth century, probably because Spanish printers of this period were chronically short of type6.

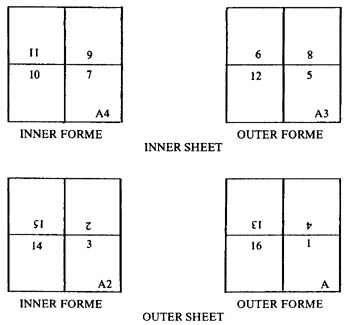

So much for «simple quarto» (Spanish cuarto sencillo), properly called «quarto in fours» in English; it was virtually the standard format for printing single plays in Spain from about 1670 to almost 1850. In the first half of the seventeenth century the standard format was the more complex «quarto in eights» (cuarto conjugado), which was used for both single plays and collected volumes. In the quarto in fours the binder's unit (a «gathering» or «quire») was one sheet; in the quarto in eights the gathering had two sheets; both were folded twice, then one was placed inside the second fold of the other. This practice halved the amount of sewing and made it easier to bind long books without bulky spines. It made life harder for the printers, however, for few of them had enough type to set a quarto in eights by pages; setting by formes (with correspondingly more casting off) was almost always necessary. The diagrams below show the layout of the pages.

Experiment with folded pieces of paper will show that the inner forme of the inner sheet could be set by casting off seven pages; the outer forme of the same sheet required eight pages to be cast off; and the inner and outer formes of the outer sheet involved eleven and twelve cast-off pages respectively. That is why the formes of a quarto in eights were usually set (and printed) in the order in which they appear in the diagrams above. This also explains why printers who were setting from an earlier edition (as opposed to a manuscript) would often follow the layout of the earlier edition page for page: it saved time and avoided mistakes in casting off7.

Once the compositor had set the four pages of his first quarto forme, he would lay them out («impose» them) in the appropriate order on the imposing stone. Round the pages would be laid the chase, a rectangular iron frame. The pages were kept separate from each other and from the inside edges of the chase by wooden «furniture». Type and furniture were locked tight by driving in wooden wedges between furniture and chase. It is important to remember that the quarto forme of type, with its four pages, was a mirror-image of the pages as they were to appear on the printed sheet.

When the forme was imposed, the compositor would take it to the pressmen, who would take the first proof, using scrap paper and (very often) an old press kept for the purpose. The first proof might be examined for «literals» (single wrong letters) by the compositor himself. This process could be done without reference to the copy. The compositor could also give the proof and the relevant part of the copy to a corrector, who would examine the proof while a reading boy read aloud to him from the copy. In this way the corrector could follow the words of the text (the substantives) as they were read to him, while checking that the compositor had supplied or normalised the accidentals (punctuation, spelling, capitalisation, etc.). The reading boy might mention some of the more notable accidentals in the copy, but he would not mention all of them. In any case, manuscript copy tended to have scanty punctuation and irregular spelling and capitalisation. It was the compositor's task to bring these accidentals up to an acceptable standard, and the task of the corrector to see that he had done so. Both would be influenced by the accidentals of the copy, especially if it were printed.

When the proof-reading was complete and the errors marked, the compositor would correct the type, following the indications of the corrector. A second proof might then be taken to verify that the corrections had been properly made. If the author or another outsider were involved in correction, it would usually be at this stage, but he would almost always have to be present in the printing-house; the modern practice of sending proofs to an author or editor caused too great a delay in the printing process to be practicable. If the second proof was satisfactory, the presswork would begin; if not, further corrections might be made and a third proof taken8. However, the manner in which Golden-Age plays usually reached the printers (years after their authors had sold them for performance) had the effect of excluding the authors and any others who cared about the correctness of the texts. Few plays can have enjoyed as many as three stages of proofing.

In some (many?) cases, presswork must have started while the last proof was still being read. Thus if we examine several copies of a book, we shall often find differences («press-variants») between the copies. In a modern printing-house this rarely happens: what are effectively proof sheets are not used in the final book. In Golden-Age Spain, however, the lower standards of printing, combined with pressures on the pressmen both to keep busy and to avoid wasting the expensive paper, meant that this occurred often enough for it to be considered a standard practice9.

While the first forme was at press, the compositor would start setting the second. In a modest printing-house, he might not have enough type to complete all four pages, and would have to wait for the first forme to be printed so that he could make use of its type. Even in the better firms a compositor would generally have to distribute type from his first forme in order to complete his third one. The implications of this are obvious: the size of an edition (number of copies to be printed) had to be decided at the outset, because it depended on the number of copies printed of the very first forme; if a firm began by printing 1000 copies and later decided that the market could take 1500, it would be necessary to print from scratch the extra 500 copies of those sheets already printed. This was so uneconomical that it was rarely done for a volume of plays.

When a forme had been printed, some of the type might not be distributed. The running headlines could be used for the remainder of the play, while recurring titles such as COMEDIA FAMOSA would be needed twelve times in a normal parte de comedias. Since much Spanish type of this period was in poor or damaged condition, it is often possible to see damaged letters and titles recurring throughout a book. This can help to prove that the book was (or was not) printed in one printing-house, while the number of different sets of running headlines in use will often reveal how many chases (and therefore, perhaps, how many compositors) were involved in a particular book. (Each quarto forme would have two verso headlines, e. g. La vida es sueño, and two recto ones, De Don Pedro Calderón de la Barca. A single set of four headlines sufficed for a single chase; two sets would imply two chases, and two chases would point to the availability of a reasonable amount of type, as well as to the possible involvement of two compositors, especially if there were supporting evidence from spelling, etc.)

When the pressmen had printed the first forme, the pile of sheets was turned, and the second forme printed on the blank side. In theory, therefore, the sheets were printed in the same order for both first and second formes; if both formes were corrected during the run, then the first sheets to be printed would have the uncorrected versions on both sides. In practice inconsistent working patterns were common.

The last sheets to be printed were the preliminaries. This was partly because they contained the errata-list and the tassa, or price, which was reckoned at so many maravedís per sheet, and which therefore depended on the length of the completed book. The tassa often carries the latest date of any of the preliminary documents, and is usually taken as the date of publication. In Castile, the other documents were the civil and religious approbations, the civil and religious licences, and the (optional) privilege, a form of copyright normally granted for ten years on payment of a fee10.

After all the sheets of a book were printed (and dried, since they were printed while damp to improve the impression), they were taken to the binder, who was usually an employee of the bookseller. At this time booksellers would not bind a whole edition at once: it would be stored in sheets, with copies being bound only as sales required. The binder's method was to lay out the piles of printed sheets in an ordered row, down which he then walked, selecting a sheet from each pile in turn until he had one of each. Thus a particular copy would consist, in theory, of the first, or tenth, or nth copy of each sheet to be printed. However, the process of hanging sheets up to dry and of collecting them afterwards, and the practice of binding only small numbers of copies at a time, tended to disrupt this regular pattern.

The pressmen would seldom produce exactly the same number of usable copies of every sheet; the bookseller would be left with several copies of some sheets and none of others. If a new edition was likely, these «extra» sheets would be kept for use in it. This happened, for example, in Calderón's Verdadera quinta parte of 1682 and 1691. The consequences will concern any editor who is making use of a corrected second or subsequent edition: if he does not notice that a sheet or sheets have been incorporated from a previous edition, he may miss some valuable corrections11.

* * *

The possibilities for error at all stages of this long process of production were almost infinite. The compositor might misread his original («misreading»); or, having read it correctly, might memorise it wrongly, adding, omitting or substituting words («memorial error»). His eye might be caught, subconsciously, by other, perhaps similar, words or passages in his text, which he might set instead of the original («eyeskip»). Such mistakes could also cause him to omit words, lines or complete passages, or even to set them twice. He could even forget to turn a leaf of his copy, setting one page twice and omitting another12.

The compositor kept his type in a wooden case divided into compartments of various sizes. Type could spill from one compartment into the next, or be placed in the wrong compartment during distribution; this caused the ailment known as «foul case». Just as a modern typist may strike the wrong key, the compositor's hand might stray to the wrong compartment («muscular error»). The composing-stick held only a few lines of type, and accidents might happen as these lines were transferred to the galley, or the galleys to the imposing-stone. Carelessness at this point could cause a whole page or more to fall into «pie» (chaotic jumble), but often only the outer ends of lines were affected. A minor example might go unnoticed, or might be corrected inadequately13.

Most of the errors so far described would be noticed during proofing, but not all. The process of correction could cause fresh errors, or fail to eliminate the old ones. It was easy to make a correction where none was required (i. e. to put it in the wrong place, especially at the ends of lines where the rhyme was the same). And since correction required the removal of the quoins (wedges) from the chase, in order to free the type for manipulation, there were further opportunities for pie or for the undesired movement of type in general. Even if a forme never had its quoins removed during printing, the irregularities of hand-cast type sometimes militated against the successful locking-up of every piece of type in a forme. Loose pieces tended to adhere to the thick and sticky ink applied by the ink-balls, and were pulled free. Their departure seems often to have gone unremarked, or they might be replaced wrongly. This misfortune could happen at any stage in the printing of a forme. If the removed pieces of type were incorrectly replaced, it might be impossible to distinguish the resulting variant from one involving press-correction.

Even if the compositor set the text correctly, the result could still be ruined by incorrect imposition. Such an error was not always easy to detect in the complex process of setting a quarto in eights. If both formes of a sheet were correctly imposed, it was still possible to produce chaos by turning the sheet wrongly when the time came to print the second side. Sometimes binders were sent instructions which might enable such errors to be patched up; but they did not always heed them14.

Of course errors could be put right after printing was completed, if anyone cared enough to insist. A whole sheet could be reprinted. Such a correction cannot be detected unless the paper or type shows some variation from that of the rest of the book, or unless some copy or copies containing the old sheet got through the corrector's net. Other possibilities involved half a sheet or (most common) a single leaf. Again, type or paper may give these away. In a half-sheet of quarto, the chain-lines or watermark in the paper may not match those in the other half of the sheet; in a single quarto leaf this may also be true, but much more obvious will be the fact that the replacement leaf will be glued to the stub of the original one. Such corrections are called «cancels», whether they involve complete sheets or parts of sheets. Strictly speaking, the incorrect original is the «cancellandum», the correct new version the «cancellans». In some cases a short passage, even a single word would be reprinted in order to be cut out and glued over the original error: this is a «paste-on cancel». Since it was not practicable to print pieces of less than half a sheet, smaller cancels would generally be set up more than once so that they could be printed in a sheet, which was cut up afterwards. Thus a single quarto leaf cancel would be set twice; this duplication of the two pages of the leaf would produce one forme of four pages. The forme would be printed by the work and turn method, and then cut into four. This happened during the printing of the Pando edition of Calderón's autos; examination of a number of copies has revealed the presence of two settings of type15.

As an alternative to cancels, there was the fe de erratas, the errata-list. This was produced by the official corrector. In theory his task was to ensure that no illicit additions were made during printing to the manuscript which had originally been approved. In practice he was reduced to compiling lists of errata. These lists are invariably incomplete -a mere token- and often have errors in page- and line-numbers; they were usually ignored by printers of subsequent editions. However, they may provide an insight into the nature of the original manuscript (except when the corrector did not consult it); and they will very occasionally supply a correct reading that might otherwise have been lost. An editor must be cautious, because some of the «corrector's» interventions served only to introduce errors16.

As a final addendum to this list of potential errors, there may be mentioned that of misbinding. Errors of misbinding will usually affect isolated copies, and should not be confused with errors of imposition, which may have similar results in numbers of copies. They are caused by incorrect folding of the sheets, or by the omission, substitution or incorrect ordering of the sheets17.

If the above catalogue of possible mishaps has conveyed the notion that printing standards in Golden-Age Spain were low, then that is appropriate. Standards declined most markedly during the very century in which most of the major plays were written: 1580-1680. They began to recover at the end of the seventeenth century, and continued to do so until a new height was reached during the Ibarra period, in the 1770s and 1780s, after which they began to fall again. We need not consider the period after 1850, when the traditional way of printing plays in Spain had been abandoned18.

The printing trade requires long-term capital investment in order to flourish, and the decline of printing in Spain is directly linked to shortage of investment19. The printers' growing indifference to the quality of their product manifested itself in the use of inferior paper, poor ink and worn type. Of course this had the effect of keeping their costs and therefore their prices down. They also adopted means of increasing their turnover: they printed more and more inexpensive comedias sueltas in the hope of selling plays to buyers who could not otherwise have afforded them; they also printed large numbers of items they had no legal right to, whether because they were still covered by copyright or because no licence had been obtained. Naturally they made attempts to conceal these illegalities, hoping to deceive the authorities. The result has often been the deception of modern editors.

One of the commonest practices was to publish plays without the author's permission. This was not actually illegal, since the person who paid for a play-text was regarded as the owner. Thus when Vergara Salcedo published Calderón's Tercera parte in 1664 without first asking permission, Calderón made some ambiguous remarks, but accepted the volume as his own20. Unfortunately, unauthorised publication often led to defective or incorrectly attributed texts. Thus Calderón rejected the 1677 Quinta parte, saying that four of its plays were not his, although only two were really by other hands21. Publishers with some sort of conscience could avoid direct lies by using such titles as Seis comedias de Lope de Vega Carpio, y de otros autores (1603). Only one of the six is definitely by Lope, but a naive customer might easily assume that several of them were. This particular volume is an octavo, and versions survive with the imprints of both Pedro Madrigal of Madrid and Pedro Craesbeeck of Lisbon. The complete background to the printing of the volume has yet to be investigated22.

The problems most likely to be encountered by editors working from printed items are as follows:

1) The unauthorised reprint of a best-seller. Piratical reprints would usually try to pass for variants of an edition already printed. However, no Spanish printer of this period could imitate an earlier edition closely enough to deceive, so the existence of a reprint can always be detected, if copies of the earlier edition survive. Telling which is which may be harder. Example: the VS Primera parte of Calderón, «1640»23. A better means of disguising the fraud was to use a false imprint; in this way an apparently authorised new edition was produced, which could not be exposed by comparison with the genuine original, and which only an expert in typography could trace back to its printer. Example: the Tercera parte of Lope, «Barcelona, Sebastián de Cormellas, 1612»24.

2) The unauthorised «reproduction» of a best-seller. Printers who wanted to cash in on a successful parte without even the cost of reprinting it would bind together twelve sueltas, print a set of preliminary leaves, and sell the resulting volume as a slightly variant issue of the genuine original. Example: the complete Vera Tassis edition of Calderón, nine volumes, «1683-1694»25.

3) The unauthorised production of the «first edition» of a parte. It was also possible to use existing printed material, whether sueltas or dismembered fragments of earlier partes, to assemble a volume which had not been published before. Such volumes cannot be detected by comparing them with a genuine earlier edition, which does not exist; but as in the previous example, they will give themselves away by their lack of continuous pagination and signatures, or (but not always) lack of typographical consistency. Examples: Doze comedias nuevas de Lope de Vega Carpio, y otros autores, «Barcelona, Gerónimo Margarit, 1630»; Parte quarenta y dos de comedias de diferentes autores, «Zaragoza, Juan de Ybar, 1650». The second of these has some typographical consistency, although it is composed of sueltas and so lacks continuous pagination and signatures26. Such a volume might be produced legally, although this will make no practical difference to the bibliographical problems. These arise from the fact that neither the date nor the printer's name on the title-page are to be relied on where the contents are concerned.

4) The desglosable, which is a play printed so that it could be fitted into any parte, depending on the market. It could even be sold singly as a suelta. A desglosable was normally fitted into three gatherings of quarto in eights. Since not all plays were equally long, one of the gatherings (generally the last) would vary in size, producing signatures such as these: A8 B8 C2; A8 B8 C8; A8 B8 C10. (In all three examples gatherings A and B are regular gatherings of quarto in eights; in the first, gathering C is a half-sheet, two leaves; in the second, two regular sheets; in the third, two and a half sheets). The play planned for the first place in a volume would be given the first three letters of the alphabet (A-C); that planned for the second place would get D-F, and so on27. Continuous pagination was usually supplied, though if it was, it reduced the possibility of switching the desglosable from one volume to another; if the pagination were to remain correct, a desglosable could be replaced only by another of the same number of leaves. It goes without saying that the preliminaries, with their list of contents, could be printed or reprinted to suit whatever went into the volume; even so, there are volumes where the contents-list does not match the plays present in the volume, or which combine fragments of true partes (not intended to be dismembered) with desglosables and with sueltas. Examples: Lope's Parte veynte y cinco, «Barcelona, Sebastián de Cormellas, 1631», and his Parte veinte y siete, «Barcelona, Sebastián de Cormellas, 1633»28. Desglosables were almost never given individual dates and imprints. It cannot be assumed that a desglosable was printed at the date and place announced on the title-page of the volume which contains it.

5) The suelta. Comedias were printed singly in Spain as early as the second decade of the sixteenth century, and continued to be printed in what came to be the traditional suelta manner until well into the nineteenth century. The total output of these three centuries was enormous. There may be ten, twenty, even more surviving editions of some plays. There are huge numbers with no imprint or date, and not a few in which imprint and date are false, whether by design or accident. In many cases sueltas are reprints of earlier editions, whether of partes or of other sueltas, which have survived. Once they have been identified as such, they can usually be ignored. Occasionally, a suelta may be a first edition (Lope's El castigo sin venganza, Calderón's Fieras afemina Amor) or an only surviving one (Tan largo me lo fiais, Rojas Zorrilla's Lucrecia y Tarquino).

6) The reissue (only technically illegal). Sometimes, when a volume's sales were declining, publishers would try to revive them by printing fresh preliminaries to make the book seem newer, or perhaps more attractive to a particular local readership. Example: Parte treinta de diferentes autores, Zaragoza, 1636; Zaragoza, «1638»; «Seville, 1638»; Zaragoza, «1639»29. At first sight, the discovery that he is dealing with a series of reissues rather than of editions might seem likely to save the editor a great deal of work; in fact he will still have to check all the copies to make certain that one of them is not a new edition. Even if this check shows that all the copies are reissues of one edition, every copy may still have its own peculiar press-variants.

If an editor is to fit a printed edition into a diagram of the history of his text, he needs to know when the text was printed and, if possible, by whom. If he does not know this, the text he is editing will be his only source of information about the habits of the compositor/s involved. Once the printer is known, it becomes at least theoretically possible to identify other works set by the same compositor. This in turn makes it easier to discover his habits and preferences, which would give rise to varying degrees of «editing» in the text being produced.

The editor should begin by collating the parte or suelta he is working on, i. e. he should note the format and check the number of leaves; doubts should be eliminated by checking more than one copy whenever possible. For example, Calderón's Primera parte of Madrid, 1636, collates as: 4°. ¶4 A-Z8 Aa-Oo8. That is, the book is a quarto. It has four preliminary leaves signed with a «pilcrow» (paragraph mark); they are followed by twenty-three gatherings of quarto in eights, signed A to Z, whereupon the alphabet is repeated as far as O, another fourteen gatherings in eights. Thus the text takes up a total of thirty-seven gatherings of two sheets each (seventy-four), plus one sheet of preliminaries. The title-page actually contains the number «75», a reference to the total number of sheets; this was a common but unfortunately not universal practice at the time. The leaves are foliated, not paginated, and seventy-four sheets (of text, since the preliminaries are not numbered) at four folios each should make 296. In fact some leaves are wrongly numbered, but the number of folios is correct. The editor can be sure that the book was planned as a unit, and is not made up of sueltas. The fact that plays begin and end in the midst of gatherings is a sign that the volume could not easily be split up into twelve desglosables, and that it was not planned in this fashion. A glance at the type shows that that used in the headings of the individual plays, in their texts (roman and italic) and in the running headlines, is consistent throughout the book. There are no suspicious circumstances about it30.

When we look for the next edition of this parte, we find two editions dated 1640. One of them, said to be printed by the widow of Juan Sánchez «A costa de Gabriel de Leon mercader de Libros», collates ¶4 A-Z8 Aa-Oo8, and has 296 folios, like the 1636 edition. There is nothing to arouse our suspicions. When we look at the other, with the same printer's name but no mention of Gabriel de León, we see that it has only two preliminary leaves, unsigned, and that the rest collates A-Z8 Aa-Ii8 KK4. The total number of sheets is only 65½, and the text is paginated, not foliated. The «75» which appears on the title-page of the other two editions is not present. If, our suspicions aroused, we investigate what has happened, we find that some preliminary matter has been omitted, and the text compressed. This is not unknown in reprints, and proves nothing. The change to pagination, which became popular in the second half of the century, is worth noting. When we look at the type, we at once find discrepancies. The type of gatherings A-L is different from that of M-Ff, while that of Gg-KK is different from both, although closest to that of A-L. Further investigation along typographical lines shows that the book was probably printed about 1670-71 by Lucas Antonio de Bedmar and Melchor Alegre; Alegre printed the middle part, Bedmar the other two, apparently with an interval between them (perhaps the length of time it took Alegre to print M-Ff). The reasons for this division of labour are not clear31.

Turning to the next edition of this parte, that produced by Vera Tassis in 1685, we again find two versions with the same date. One collates ¶8 ¶¶6 A-Z8 Aa-Ll8 Mm4, and the text is paginated from 1 to 543 (544 is blank). The typography is reassuringly consistent. When we try to collate the other, we find it impossible: signatures begin afresh with each of the twelve plays; so does the page numbering, when there is any; and the typographical variations are enormous, with differences even between copies. In fact the volume is composed of twelve sueltas which are the work of several firms. Different editions of some sueltas were used in some of the different copies. External evidence shows that the fraud dates from about 1700-1710, but of course some of the sueltas may have been printed much earlier than this. The only sure way to discover their dates is to take them singly and rely on typographical evidence32.

It must be emphasized that not only reprints were produced by work-sharing or by making-up. For example, there is evidence that the first edition of Comedias escogidas XXXIII, 1670, was begun by Melchor Alegre and completed by José Fernández de Buendía, although naturally the title-page does not furnish this information33. In the so-called Diferentes series, partes XLII, XLIII and XLIV, ostensibly printed in Zaragoza between 1650 and 1652, are all composed of sueltas, although no earlier editions are known. Not all copies of XLIV have identical contents34.

We come now to typographical evidence which, as stated above, is the only sure way of discovering the real date and printer of a book with no, or with a false, imprint.

Most printers in Spain gave up using gothic in favour of roman type in the third quarter of the sixteenth century. Thus the great majority of Golden-Age plays, and all of those from Lope de Vega onwards, are printed in roman type. Typographical material has always been expensive, even when labour was cheap. Typemetal alone cost one and a half reales per pound, and casting cost four and a half reales per 1000 pieces. A minimally useful fount of pica (about twelve points today, and the size most frequently used for plays in the seventeenth century) would weigh upwards of 200 pounds and involve 50,000 or so pieces, at a cost of rather more than 500 reales; if constantly used, it might not last a year. A set of matrices with a type-mould, which would enable a properly trained printer to cast his own type, was likely to cost much more than 1000 reales for a text-type, to which had to be added over 300 reales for a usable amount of metal. Once purchased, the metal would last indefinitely, but matrices and moulds eventually wore out. In any case, both matrices and skilled typefounders were scarce in Spain.

Given the parlous state of the Spanish printing industry, few printers could contemplate such major capital outlays often enough to maintain high standards. Their typographical material was generally worn, damaged, adulterated and improvised. They got type from where they could; seldom concerned to get the best, they got instead what was most readily available. The result is that in much of the Golden Age, the typographical material of each printer was relatively distinct.

During the period in question, Spain's chief sources of type were France, the Low Countries and Italy. Type deriving from the French designers, Garamont, Granjon and Haultin, was everywhere common, and predominant in Madrid. Printers in the Seville area enjoyed the benefits of shipping links with the Netherlands, and so had a higher proportion of type deriving from the Flemish punchcutters François Guyot, Ameet Tavernier and Hendrik van den Keere; after 1648 they also got type from Dutch foundries, some of it Dutch (e. g. Christoffel van Dijk), some of it of German origin (e. g. Voskens of Hamburg and Berner of Frankfurt). In the kingdom of Aragón there was less Flemish, Dutch or German type, at least during the seventeenth century. The type there was largely French, with some Italian, e. g. from the Vatican foundry.

Apart from providing evidence about the whereabouts of a book's printing, type also helps with dating. In some cases we know when a design was produced; in others we know when it arrived in Spain. The 13mm capitals of the Vatican foundry were first used in Italy in 1612-13 and in Spain about 1619; Spanish books which appear to use them before 1619 (and certainly before 1612-13) should be regarded with suspicion. Similarly, three sets of capitals were cut in Madrid about 1685 by one Pedro Disses35. Books which use them before this date are frauds; for example, the fake Vera Tassis versions of Calderón's Sexta and Séptima partes (1683) could be rejected for this reason alone.

The easiest method of identifying the date and printer of a suspect or imprintless item is to draw up a list of its typographical material, from the largest roman to the smallest, the largest to the smallest italic, and finally of the ornaments, whether they are made of metal or of wood (it will not always be possible to distinguish wood from metal; but if an apparently identical ornament is used more than once in the same forme, then it will almost certainly be metal). If the design can be identified from the various facsimiles of old founders' specimens, so much the better: this may provide information about dates and places, as suggested above36. If a typeface or ornament cannot be identified in this way, the investigator will need to obtain a photocopy of it for comparison. He must then look for books which use the same typographical material in circumstances which give rise to no suspicion. This is the hardest part of the process, particularly for someone with no access to large numbers of old books. If the investigator has no evidence to help him limit the initial scope of his search, the task may be impossible. It is true to say, however, that any intelligent and observant person who examines the type of a sizable number of old books will become reasonably good at guessing when an undated one was printed, and eventually where it was printed. Besides, the increasing availability of facsimiles and microfilm collections of old books makes it less and less necessary to consult the originals37.

There will be many cases when it will not be necessary to establish exactly when an edition was printed, and by whom; that is, a guess such as «Madrid, 1660-1680?» will often be enough to establish the chronological relationship of that edition to others, a relationship which textual evidence will usually confirm. Only in cases when such an edition is to be used to establish the text will it be necessary to investigate further the circumstances of its printing.

Some rules for the dating of imprintless sueltas were set out by Edward M. Wilson in 197338. Since they have been refined and added to in the past decade, they will bear repeating here. Further research will certainly produce more refinements.

1) Format. Quarto in eights became the standard format for partes and for sueltas during the second decade of the seventeenth century; for partes it remained so, with rare late exceptions such as the Apontes edition of Calderón. Sueltas, on the other hand, switched from quarto in eights to quarto in fours during the years 1650 to 1670. Further research is desirable, but a suelta in eights will probably be early, perhaps before 1650, while one in fours will probably be later, perhaps after 1670.

2) Title-pages. As a rule, sueltas had individual title-pages only in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, but a few sueltas were given title-pages both earlier and later than this. Some of the later ones may be special editions linked to first performances (like Calderón's Fieras afemina Amor).

3) Serial numbers. Sueltas began to have serial numbers about 1700. Some valuable research has been done on these numbers; it has been shown, for example, that neither they nor dates are entirely to be trusted. Some reprints were given the old serial number and a new date; others reprinted the date along with the rest, and can be identified only by type and paper39.

4) Spelling and punctuation. During the period when sueltas were being printed, there was a gradual but uneven progression towards modern spelling and punctuation. The investigator will soon get used to noticing the changes, although their uneven nature makes them difficult to use for precise dating. Printers in Seville, with their access to the new Dutch designs, began using J and U (for consonantal I and vocalic V) in the 1670s; this change did not become widespread in Madrid printing until the 1690s. The adoption of short s and inverted punctuation (¿¡) belongs to the second half of the eighteenth century, although it varies from printer to printer; further research is needed. The use of :: or ::: or ::- for modern three points [...] had a brief vogue in the mid eighteenth century. A lot of research remains to be done on ordinary spelling habits, e. g. on when the printers stopped using initial «y» for «i» or «ç» for «z».

5) Size and design of type. Plays were usually printed in pica (lectura or cícero) in the seventeenth century; the size of body varied from 79 to 89mm per twenty lines. The larger bodies are particularly associated with Madrid founders in the second half of the century. Naturally Madrid printers used the type of Madrid founders, but Madrid type was used further afield as well-sometimes even in Seville. Seville printers were printing plays with text-types of 65-69mm/20 lines (long primer, entredós) in the 1670s, but sizes in the 70-79mm range (small pica, lectura chica) are associated with the very end of the seventeenth and with the eighteenth century. The practice of printing some gatherings -usually the last one- of sueltas in smaller type in order to fit them more neatly into a whole number of sheets seems to have begun at the end of the seventeenth century. This was just when small pica was coming into regular use (usually pica and small pica are the two faces involved). It should not be confused with the practice of using two different founts of pica in one play, a practice which almost certainly points to two compositors. Measurement of the body-size will prevent confusion. Apart from text-types, titling types can also help in dating, as already pointed out. There was a constant influx of new titling types into Spanish printing during the Golden Age. In some cases, the date of production of the original designs is known; in others, the date of their introduction into Spain has been deduced. In many cases only the experience of looking at dated books will allow the investigator to become adept at guessing the dates of undated items40.

6) Paper. Too little research has been done on Spanish paper, and in particular on that of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The investigator who hopes to use paper as evidence in dating will have to gather much of the basic information himself. The task will be complicated by the fact that sueltas were frequently printed on poor paper, which the manufacturers did not always watermark; and by the fact that not all watermarks can be trusted, since a lot of imported paper bearing the Genoese mark was really produced in Holland. However, the one serious attempt to date sueltas from paper shows that some of the difficulties can be surmounted, and that evidence from paper, if applied in the proper circumstances, can be valuable41.

* * *

After this long preliminary, we may now return to the consideration of the seven different parts of the author's task, as set down at the beginning.

In recent years two major bibliographies of Spanish Golden-Age dramatists have appeared: M. G. Profeti's Per una bibliografia di Juan Pérez de Montalbán, and the Calderón-Handbuch of K. and R. Reichenberger42. In theory these list all the known editions of the work of the authors concerned, and the whereabouts of all known copies of the earliest editions. In practice, of course, a bibliography is almost by definition incomplete, but these two works are indispensable starting-points for any textual study of Pérez de Montalbán or Calderón. There exist various other bibliographies of Spanish Golden-Age dramatic literature, some dealing with authors, some with particular collections, with individual volumes or with particular plays. Of special usefulness are the various catalogues of comedias sueltas which have appeared in the course of the last half-century43. Not all libraries, especially in Spain itself, have published catalogues, however, and editors must be ready to contemplate writing to and even visiting some of them to ascertain what their holdings are.

When the editor has completed a list of all known early editions of his play, he must arrange them in a stemma, i. e. in a family tree. Mere chronology, once it has been established in accordance with the information given above, will provide a starting-point, but it should be confirmed from textual evidence. For example, close examination of any early edition of a play will reveal misprints and obvious errors, no matter how carefully it was produced. When such an edition was reprinted, the compositor would automatically correct obvious errors. Sometimes he would miscorrect an error, and as compensation for his successful corrections, he would introduce fresh errors. All this will seem very clear when the precedence of the one text over the other is certain or nearly so. When it is not, the matter is quite different. It is sometimes very hard to determine, from textual variants alone, which of two closely-related prints of a play is the earlier. If there is a reasonable interval between them, older fashions in spelling, punctuation and capitalisation will point (though not infallibly) to the earlier. If the practice of the author himself is well documented in these areas, one can usually assume that successive editions will diverge more and more from it. If one of the editions omits anything which is present in the other, the more complete version is likely to be the earlier, since compositors' corrections did not as a rule extend to making good omissions. None of these methods is entirely reliable. It may be said, though, that if an editor is faced with a pair of texts (say, two sueltas) so similar that he cannot tell which was printed from which, he should not worry, since it cannot be very important. In most cases such a pair of editions will occur well down the stemma, where they can have no bearing on a definitive text; if they happen to constitute the first and second editions of the play, it will hardly matter which is chosen as the copy-text: any differences significant enough to be of importance in a definitive edition will provide evidence of precedence.

To a certain extent, the process of investigating relationships between texts can be reduced to a formula. The example most readily available to readers of English is Sir W. W. Greg's Calculus of Variants (1927), which W. F. Hunter has shown how to adapt for Spanish dramatic texts44. Greg shows how to interpret the evidence of different groups of variants, and is well worth any editor's trouble to read. However, his method was intended to be used, and is most useful when dealing with manuscripts, such as we find among Calderón's autos. Undated manuscripts can rarely be dated with any precision, unlike a printed edition; every manuscript is unique, and since unique items are easily lost, we rarely find an example of manuscript transmission which has no manuscripts missing. Printed editions disappear less frequently, and since most are dated or datable, much of the task of establishing relationships can be done by simple chronology, without recourse to formulae. Any editor who feels apprehensive should examine the introductions of a few reliable editions, or read some of the number of appropriate textual studies. The best of these give examples of how progressive corruption and/or correction can be detected in successive versions or editions45.

An editor with access to a computer will be able to do the more mechanical parts of his task with greater speed and accuracy. Computers have already been used to compare different versions of a text to find variants. The versions are typed into the computer, which is programmed to produce a variant-list; if the typist is guilty of errors or omissions, these will be recorded as variants, and the faults can be put right by checking the originals. Only if the same error is repeated in the typing of the different versions will difficulties occur, but even this can be eliminated by proper checking. Nowadays, however, it is not necessary to type the texts: some computers can read print. Furthermore, computer programmes can be written to do the more mechanical parts of classifying variants according to Greg's Calculus. In the last resort the editor will still have to use his own judgement to assess the priority of one text over others, but he will have saved a good deal of time46.

A version of a text which must have existed but now does not is called «inferential» (because its existence can be inferred). The commonest inferential version which an editor will encounter is the author's original. There may sometimes have been cases of composition by dictation, but for practical purposes we can invariably assume, with no evidence but a printed edition, that a holographic original once existed. Other inferential texts will require more evidence. Dates, places or other features of the wording of a book's preliminaries may lead us to suppose that the earliest known edition is not the first. This is true of Lope's Tercera parte, which probably appeared first in 1611, in Valencia47. Alternatively, an edition of, say, 1650 may vary so much from one of 1620 that an editor may conclude that another intervened. These are risky arguments, however; generations of editors have created hundreds of ghosts (editions which never existed) by misuse of them, the most notorious being the «1604» Don Quixote.

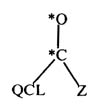

A more trustworthy method of identifying inferential versions is from textual evidence. Consider a text of which two editions appeared more or less simultaneously in different places. They vary too much to have been printed one from the other without revision; each has lines not present in the other, but yet they share errors or areas of textual confusion, such as an author is not likely to have produced. We can infer a common ancestor which contained these errors or confusions, and which was therefore not the author's original. We can infer also, as usual, the existence of a version which was in the author's hand. The stemma would look like this:

This is the stemma of La vida es sueño, where *O is Calderón's original, *C the inferential common ancestor, QCL the Madrid edition and Z the Zaragoza one, both of 1636. The stemma is complicated by Calderón's revision, prior to the existence of QCL, but after that of *C, of what he wrote in *O. (That is, his original version reached Z via *C, his revised version reached QCL via *C). Zaragoza is far from Madrid, so it seems unreasonable to suppose that *C served as printer's copy in Zaragoza, found its way back to Madrid to be revised, then served as printer's copy for QCL; it is also unreasonable since there is some evidence that both books were being set at the same time. So we can infer another version; presumably it intervened between *C and Z or between *C and QCL. We cannot say which, and cannot place it in the stemma.

Another means of detecting inferential versions is through accidentals, mainly spelling. If we had a parte of twelve authentic comedias by one author, of which one betrayed spelling peculiarities not found in the others, we could reasonably conclude that the play had not been set from the author's original -reasonably, that is, once we had eliminated the possibility that that play had been set by a different compositor.

Detecting inferential versions of a text is a necessary part of drawing up a stemma: it will enable the editor not merely to discover which surviving version of his text is nearest to the original, but how near it is. This is important, since the kind of edition produced, and the extent of the editor's intervention, will to some extent depend upon it. It may be said, as a general rule, that the nearer an editor's basic text is to the original, the less he will tamper with it.

Sometimes a stemma

will turn out to be a simple line: edition 2 produced from 1, 3

from 2,4 from 3, and so on. If that is so, edition 1 will provide

the basis, even if subsequent editions have been revised or

corrected. This is an important principle, with all the

authority of Greg and McKerrow behind it: «in all normal cases of correction or revision

the original edition should still be taken as the

copy-text»

48.

«Normal cases» means those where revision or correction

are carried out by marking-up a copy of the first edition and

giving it to the printer as copy for the second.

«Abnormal» cases might involve those in which the

author re-transcribed the work as he revised it, giving the new

autograph manuscript to the printer. But how to tell the normal

from the abnormal? How to choose between two independent editions

of ostensibly equal weight, as in the stemma illustrated above? For

that matter, how can one distinguish an authentic authorial

revision from an unauthorised and unauthoritative compositorial

alteration?

No editor should set out to prepare an edition of any author without first having read a great deal of the work of that author and his contemporaries. (If the author wrote only one play, the editor must make do with the contemporaries, although this will be a poor substitute). An editor who is thoroughly familiar with his author will often be able to reject some «corrections» as merely compositorial, while accepting others as authentic. This may not sound very scientific, but it can be made more so by quoting chapter and verse for other examples, found in other works by the author, to support the authenticity of words, metaphors, turns of phrase and even verse-forms49. The growing number of concordances, metrical studies and linguistic analyses being produced for Golden-Age authors will greatly simplify this operation.

All this involves the substantives of a text. Of equal importance are the accidentals: spelling, punctuation, capitalisation, accentuation, lineation. Nowadays we have rules governing such matters. The rules are relatively strict, but they allow for some individual preferences in the use of some signs of punctuation, some spellings (-ise versus -ize, etc.), and permit us to detect, if only on a global scale, regional variations (labor, labour, theater, theatre, etc.). To the untutored reader, written Spanish of the Golden Age may seem to have had no such rules, but this is false: the rules were there, but they were less strict, and thus gave a wider scope to individual preferences. To complicate matters further, there was a considerable variation between the rules as applied to printed Spanish and as applied to the handwritten language (this variation is still with us, in that we expect the printed language to adhere more closely to the rules, and, where the rules are flexible, to be consistent: hence the need for journals to provide contributors with style-sheets). Spanish writing-masters, if they did not provide specific recommendations regarding spelling, punctuation and capitalisation, would advise their pupils to imitate the usage of good compositors50. It is clear, however, that many authors, even when they wrote with publication in mind, paid scant attention to such advice; they expected the printers to be their sub-editors, to be final arbiters of what was correct51. In practice, the printers, working as they were within a flexible set of rules, and from manuscript material written according to even more flexible rules, never managed to impose an absolute degree of consistency. For example, at least part of Calderón's Quarta parte was set by two compositors, who tended to do two pages each of every four-page forme. They are most easily distinguished by their spelling of the name Deidamia, a character in El monstruo de los jardines, the third play: one preferred Deidamia, the other Deydamia. The Deydamia compositor also preferred the spellings boluer and fè, his companion bolver and fee. When the parte was reprinted in 1674, corrections and alterations meant that it did not follow the old edition on a page-for-page basis. Nevertheless, the new compositor or compositors were influenced by the spelling of their copy, even changing from Deidamia to Deydamia in mid page. Given the tendency exemplified by this case, editors should always consider the possibility that variant spellings in a given edition may not point to two or more compositors in that edition, but may derive from an earlier edition, or from two or more scribes (or even authors) in a manuscript.

Both Lope de Vega and Calderón have left large amounts of autograph material, covering the greater part of their careers. The investigator has the wherewithal, if he wishes, to discover the preferences of these two authors with regard to accidentals at almost any stage of their writing lives52. Indeed, it would be possible, within certain limits, to reconstruct the appearance of a word or phrase written by Lope or Calderón at most stages of their careers. For most other authors this will be harder, sometimes impossible; but it is important that an editor should know, in so far as he can, what the autograph manuscript of his author's play would have looked like. The reason for this is that personal peculiarities of handwriting, together with personal preferences in spelling and other accidentals, would combine to produce a unique document. If these peculiarities and personal preferences were such as to cause difficulties in decipherment and therefore, in some cases, errors, the errors in their turn might be peculiar to one author or, at least, characteristic of him. Once an editor is aware of the way in which such characteristic errors were made, then he stands a chance of reversing them with some degree of confidence53.

As pointed out above, successive copyings or printings tended to dilute the accidentals of the author's original. As a general rule, if an author's accidentals are very eccentric, and these eccentricities are largely preserved in a printed edition, that edition is unlikely to be far removed from the author's original. Naturally, the eccentricities which have the best rate of survival are those involving rare words or proper names: scribes and compositors, unsure of the «correct» spelling of a rare word or of the identity of a proper name, tended to preserve the spellings they found54.

The extent to which compositors impose their own style upon their copy will, of course, vary. This is one of the ways in which compositors can be identified. The painstaking researches of Dr. R. M. Flores on the text of Don Quixote have shown that the whole printed page, including type and the spaces between, is of statistical value in this respect. Compositors had differing preferences in spelling, capitalisation, punctuation, accents, abbreviations, spaces (particularly in association with marks of punctuation); the width of the type-measure, the number of lines per page, the positioning of signatures and catchwords: all these are variants which can provide information about compositors55. If, as sometimes happened, different compositors set their type from different cases, the condition of the type might vary, as might the availability and even the design of different sorts; the recurrence of damaged and identifiable individual sorts, and the intervals at which they recur, can also provide information about how a book was set up56.

The availability of certain sorts of type is particularly connected with plays. Plays generally contain a high proportion of capital letters (because of the many short speeches and proper names), as well as of queries and exclamation marks. More than the usual amount of italic type was needed for speakers' names and stage directions. Compositors tended to run short of certain sorts (especially queries and italic capitals). Instead they used roman capitals and improvised queries by turning semi-colons upside-down. It will often be possible to discover the order in which pages were set, or to guess at the amount of type available, by noticing at what point the compositor began to show signs of running out of some sorts. Unfortunately, investigations of this kind will be complicated by the fact that composition was sometimes held up while the compositor waited for the pressmen to print an earlier forme which he could then distribute to get fresh type57.

The purpose of all this kind of investigation is to help identify the editor's basic text, and the extent of the compositor's «editorial» intervention in the printing of it. It will also reveal textual problems, ranging from obvious errors and omissions to obscure passages which may be made to yield sense. In the majority of cases the editor will have other editions to which he can turn for help in solving the problems. There is no point, however, in adopting suggestions from other editions without knowing how much authority they have. This brings us to section four.

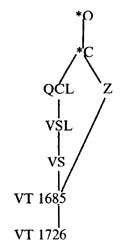

If the stemma has been drawn up correctly, it will often be immediately obvious which versions of the text are most likely to be of use in correcting errors in the basic text. Versions which derive directly from the basic text cannot have readings with more authority than it has, unless they have been corrected by the author or by someone with access to another version. (This does not mean that directly-derived versions are of no use; the attempted corrections of another editor, even if they have no authority but his own, can often help to resolve, or at least to cast new light on, textual cruces or editorial problems). The most helpful versions will be those which are not far removed from the author's original, but of which the line of descent diverges from that of the basic text. This can be illustrated with reference to the stemma of La vida es sueño:

The stemma has already been discussed down to QCL and Z. VSL is a relatively close reprint of QCL, reproducing some errors, correcting others, introducing a few errors of its own58. There is no evidence of an authoritative attempt to correct the text, although the nominal editor, Calderón's brother José, was alive in 1640. As we have seen, VS was really produced about 1670, when Calderón at least was still alive. It was printed from VSL, since it makes some errors which can derive only from VSL, but it has more ambitious corrections than the latter; these may be Calderonian59. The first Vera Tassis edition of 1685 was printed from VS, but there is evidence that Vera also used Z; apparently he had no other source60. Finally, the second Vera Tassis edition was produced in 1726. The date of Vera's death is not known, but he was almost certainly dead by then. There is no sign of any serious attempt at correction in the reprint.

The 1726 edition, for practical purposes, is of no use to an editor. The 1685 edition, although it shows how Vera tried to produce correct texts, has no more authority than the still extant texts from which it derives. We may consult Vera to see how he tackled an error shared by QCL and Z; we may even adopt his suggestion; but we must remember that there is no proof that it is anything but his suggestion.

The stemma reveals that the only authoritative texts are QCL and Z, which, because they have a collateral relationship, offer a real hope of reconstructing the lost *C. The few possibly authentic corrections in VS are not shown in the stemma because of the doubts about their origin. In any case they are too few to be very significant.

As stated earlier, QCL represents a revision of the text, Z the original version. If we are to adhere strictly to the recommendations made by Greg with regard to the editing of revised texts, our procedure ought to be to take Z as our basis and revise it from QCL. In fact no editor has ever done this; many have ignored Z, and those who have used it have taken QCL as the basic text, adopting selected readings from Z. This is not entirely satisfactory; the business of knowing when to correct a basic text by adopting a reading from another one is such an important part of editing that it is best to adhere, as far as possible, to a good set of principles. Greg offered a set of principles for the guidance of authors in precisely this kind of case. When the fact of revision is established, he said,

It must not be

thought, however, that adherence to such principles will make the

whole process automatic and release the editor from the need to

think: «No juggling with copy-text will

relieve him of the duty and necessity of exercising his own

judgement»

61.

A few cruces from La vida es sueño will serve as examples. In lines 1600-2, QCL has:

|

This is pretty meaningless. Where QCL reads «sus ruinas», Z reads «las minas». If we take Z as our basis, we should conclude (1) that the original reading (las minas) can reasonably be attributed to Calderón and (2) that the later reading (sus ruinas) is not one that can reasonably be supposed to have been substituted for the former. The Z reading is therefore retained, on the assumption that «preferir» here means «to take precedence», a sense that can be supported from other passages in the play. (In practice modern editors who have taken QCL as their basis, but who have consulted Z, have adopted Z's reading. This illustrates an important editorial maxim: good sense can make up for faulty principles. Contrariwise, even sound principles will not compensate for a lack of good sense. Best of all is to have sound principles and to apply them sensibly). In line 448, we find that in Z Clotaldo says that honour

|

while QCL reads «facil» for «fragil». At first sight this example appears to be like the previous one, in which QCL makes nonsense of a good Z reading. However, a glance at the Diccionario de Autoridades reveals that «fácil» can also mean «frágil», while in La cisma de Ingalaterra we can find a description of a moth flying round a light

|

| (400-12) | ||

This is really a case in which the answer to both Greg's questions is affirmative, so we must conclude that QCL's reading is Calderón's own revision. There is a similar case in line 631, where QCL reads

|

while Z offers «iluminan» for «campean». «Campear» means «to light up» here; it is recorded in Covarrubias's Tesoro, and Calderón's use of it is confirmed by a glance at the Hamburg concordance of his autos, which records five occurrences.

As it happens, if we knew nothing of the relationship between QCL and Z, but were simply presented with these two choices, we would opt for the readings «fácil» and «campean» on the principle of «lectio difficilior melius». That is, we would choose the more difficult word on the assumption that an unauthorised change is much more likely to go in the direction difficult-to-easy than vice-versa. The authenticity of the readings would of course need to be supported, as in these two cases, by Calderón's use of the words elsewhere.

So far, so good; but, as already indicated, these principles do not absolve us from the need to think and, indeed, do not always solve the problems for us. For example, in one of the well-known speeches at the beginning of the play, Rosaura refers to Segismundo's tower thus:

|

| (QCL. 56-8) | ||

Later, Clarín puts forward the suggestion that

|

| (QCL. 67-9) | ||

There is no feminine noun to which «ella» can refer. If we look at Z, we can see what happened:

|

The application of Greg's principles will lead us to conclude that Calderón himself revised lines 56-8; there is a nice irony (which will become apparent later) in the use of «Palacio», and even «nace» is more in keeping with the preoccupations of the play. However, if Calderón revised line 68 to take account of the change in gender of the key noun, his revision has not reached us; in fact it is more likely that he overlooked it. If we change «ella» to «él», we need a hiatus to produce eleven syllables; what are we to do? The answer must be that we retain «ella», since we have no evidence that Calderón ever wrote «él», and that we draw attention to the problem in a note. This is a «solution» which the editor will often find himself obliged to adopt.

Sometimes the editor will find problems more intractable than this. Sometimes he will find that no versions exist which can be used to correct flaws in the basic text (there may be only one surviving version, or all the versions may be obviously wrong). In such cases the editor should consider making the correction on his own authority. At the simplest level, this may involve putting right an obvious misprint, but other, more complex corrections are bound to arise. The editor will be less likely to err if he bears four points in mind: 1) modification of the readings of a basic text should not be undertaken lightly; 2) no editor should adopt a reading from a version other than the basic text without some idea of how the reading reached that version and without some evidence that it could be authentic; 3) where there are two readings of apparently equal authority, it is better to adopt the one which can be supported from other occurrences in the author's work; and 4) if the editor concludes that the correct reading is not present in any surviving version in which the author might have intervened, but that he or another editor has reconstructed it, he should at least consider what mechanism produced the error from what he thinks is the correct reading (i. e. misprint, misreading or any of the other causes mentioned earlier); if the error is inexplicable, he should think again63.

Editors of classical English plays have access to a number of series in which their editions may be published. These series usually have general editors who exercise a close control over the kind of edition which is produced. For practical purposes this situation does not operate in the field of Spanish drama. As a consequence, decisions about the kind of edition to be produced are largely to be taken by the individual editor64.

The editor's options are theoretically numerous, but can be reduced to three basic ones: 1) an edition which preserves all the accidentals of the basic text (spelling, capitalisation, accentuation, punctuation, lineation); 2) an edition which preserves some accidentals but not all of them; 3) an edition which modernises all the accidentals. Until the twentieth century, an editor would hardly even consider producing a text with the original accidentals. As the century has advanced, more and more editions have been produced with some of the accidentals (usually spelling) preserved; there are still relatively few which retain all the accidentals65. Since we are dealing here with printed sources, it is as well to reiterate the crucial point that in a printed edition the author's original accidentals will already have been modified.

An author's original accidentals are sacrosanct only in so far as they are a guide to what the author intended to say, and as a source of information for editors of other plays. If his accidentals are eccentric both by his contemporary and our own modern standards, no editor can be expected to retain all of them once he has extracted his information from them and made a note of them for the enlightenment of other editors. For example, in lines 13-14 of Act III of his play En la vida todo es verdad y todo mentira, Calderón wrote:

|

The points before and after the first «de» were evidently meant to indicate a verb in the subjunctive as opposed to a preposition; an efficient seventeenth-century compositor would have omitted them in favour of an accent on the «e», just as a modern editor should. But how to decide between the accidentals of an efficient seventeenth-century compositor and modern practice, when these vary? Here we must weigh up the losses and gains.

The accidentals of printed Spanish in the Golden Age were essentially rhetorical rather than the product of grammatical logic, as is now the case. That is, they were more concerned to preserve the emphases of speech than to aid the thought-processes of the modern silent reader, as this quotation suggests:

|

es de saber que enel razonamiēto, y comun hablar nuestro, acostumbramos hazer (como cada vno vee) ciertas pausas, o detenciones: y estos [sic] siruen assi para que descāse el que habla, como para que entienda el que escucha. Y es de notar que no se haze pausa dōde quiera, o siempre que al que habla se le antoja, antes bien en cierto lugar y paradero, que es en fin de sentencia perfecta, o imperfecta: y desta perfection o imperfection nasce ser mayor o menor la pausa y descanso del que habla. Como la escriptura no sea otra cosa que vn razonamiento y platica con los ausentes, hallan se tābiē enella las mismas pausas y interuallos señalados con diuersas maneras de rayas, y pūtos66. |

A system of accidentals intended to preserve the emphases of speech cannot but be relevant to the editor of a play. An editor should therefore devote serious thought to preserving the two accidentals involved, i. e. punctuation and capitalisation. If his projected edition is of the scholarly kind, then preservation is extremely desirable; but if it is «popular», then preservation of these accidentals may be regarded as eccentric and even counterproductive.

Spelling is in a somewhat different category, in that the original compositors tended to preserve far more of the author's own than of the other accidentals. Complete modernisation of spelling is always undesirable, for it will obscure distinctions or similarities of rhyme and metre which should be preserved. Thus if we add «p» or «c» to «conceto» or «perfeto», they will no longer rhyme with «discreto»; if we modernise «mesmo» to «mismo», it will no longer assonate with «lecho»; if we change Calderón's spellings «agora» and «aora» to modern «ahora», we disguise the fact that he always used the first for three syllables, the second for two; if we change «Ingalaterra» or «corónica» to the versions now current, we may create short lines, and so on. Even in cases where rhyme and metre are not involved, we may spoil jokes and puns, as in the case of Sancho's remark about «el yelmo de malino», where modernisation to «maligno» obscures the already feeble joke67. Even in popular editions, therefore, some spellings must be retained. The editor can adopt one of two rules: 1) retain all spellings where modernisation might adversely affect either the meaning or the metre, or 2) retain all spellings which might imply a pronunciation different from that implied by modern spelling. The second of these is probably preferable, since it is safer: even a careful editor may fail to notice puns or jokes. However, even the second rule is potentially imperfect, for there will be cases where differing spellings have the same pronunciation, and modernisation can help to obscure a point. In a scholarly edition this problem can be largely avoided by preserving the original spelling68.